The end of Google Reader is yet another reminder of just how much our lives depend on services that exist beyond our control.

Written by Michael Thomsen (@mike_thomsen)

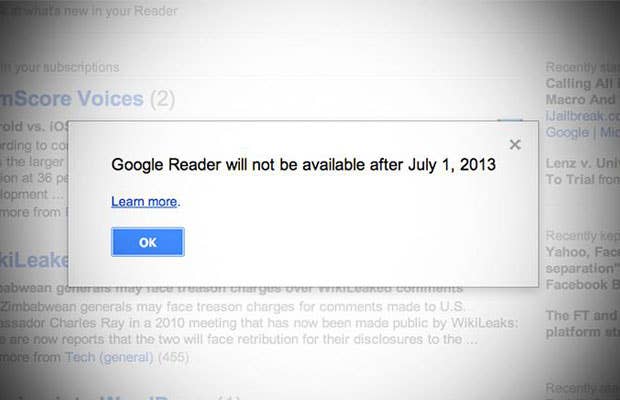

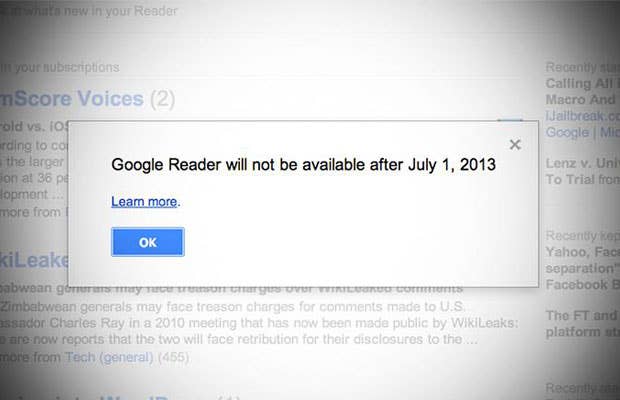

Progress is only exciting in the first stages, when a fanciful idea becoming an attainable thing is most delightful. But if progress exists, it must also be maintained over long periods of time, to ensure its benefits remain in place even for those who've forgotten they're there. This week Google announced it will be closing its Reader service on July 1 for "two simple reasons," a decline in users and a desire to focus on a smaller number of products in the future. For many in the West the news was a reminder the dusty old service still existed, having long been surpassed by a number of reader alternatives more flexible and responsive to the increasingly varied habits of, and devices for, internet reading.The closure is also a reminder that progress always has a point of view, identifying groups of people as an audience worth serving while implicitly identifying others as unworthy.

While Reader's ideals of serving and centralizing content became less and less useful to Westerners, it came to play an important role in countries like Iran and China, where the government's heavily censor what is available online. As Quartz's Zachary M. Seward points out, Reader was an ideal way around government interferencebecause of its dependence on Google servers to aggregate each feed from their originating sites, and then send the list as a whole to a user. If the government had imposed a ban on users accessing a particular website, Reader offered a work around, pulling its content into Google's servers. To block prohibited material from getting through Reader, governments would have to interfere with access to other Google services, which sometimes happened, but was always greeted with hostility.

Like the closure of Labs before it, Reader's servers going offline is a clear instance of a company choosing marginal profitability over servicing a public good that has become boring.

"In a country which all social website like twitter, facebook, friendfeed, and video or image sharing websites like youtube, tumblr, flickr, picassa and many more are banned," one Iranian writer argued, "Google Reader acts like a social websites and in lack of any independent news website (it should be mentioned that all international news channels like BBC, CNN, VOA, and all other non-governmental news website are banned,) Google Reader acts like a news spreading website. Easy access to Google Reader made it suitable for Iranian community and through all these years, specially after June 2009 election, developed an strong community for spreading the news."

John Pavlus points out Reader was a product of Google Labs, the company's now closed department focused on inventing things with no imposed constraints on profitability or utility. In the intervening years, profitability has become its own feedback loop, with progress pegged to a company's ability to make money from it. This is not technology as a means to improve the human condition, nor offer resources to those in countries who lack them. When companies like Google advertise their products in terms of human beneficence, they are eliding the underlying products are privileges made possible by the political and economic conditions of the country whose legal framework they depend on for profit. And when put in a pinch, they will not side with users with a valid, ethical case.

Like the closure of Labs before it, Reader's servers going offline is a clear instance of a company choosing marginal profitability over servicing a public good that has become boring. It's a reminder of just how much of our lives depend on services that exist beyond our control, things we've internalized and taken for granted, like the ability to always call home, or to be able to look up an address and map while you're already en route. These are not technologies we own, they're privileges given us as justification for consumer loyalty, and the driving logic behind them is not progress but creating an aura of inevitable consumership, a techno-haze that makes it impossible to imagine life without them. It's progress as dependency.

We have better things than Google Reader now, but "we" is not all that inclusive in this case. And companies like Google only want to be in the it-gets-better business when there's a profitable enough audience. In reality, these forms of progress are always conditional, temporary advancements that recede as soon as those in Western markets have grown bored of them, and before they have had a chance to do anything of worth for the rest of the world.