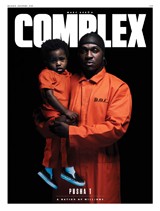

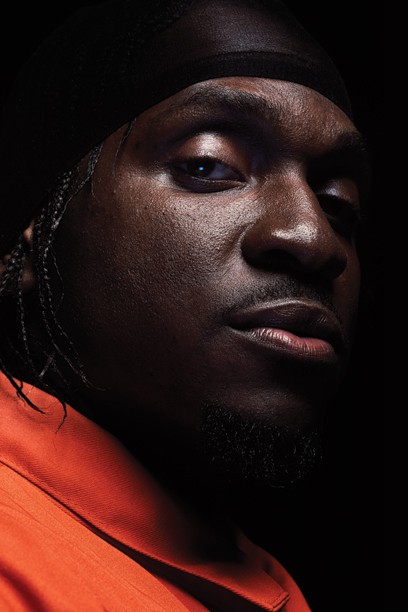

When he was 8 years old, Terrence Thornton knew that the quickest way to get his older brother Gene’s attention was to target what he prized most: his book of rhymes. “He wouldn’t pay me no attention or no mind, so I’d go straight for his rap book!” he says, acting out the scene with his now 39-year-old body, arms considerably longer and thicker, flesh tattooed. He makes his voice squeak a bit for greater effect. It’s a funny scene to imagine—first, because it’s hard to picture it ending with anything other than an ass whooping. But also because of the irony of Terrence growing up to become Pusha T, one of today’s best and most respected writers in hip-hop.

Pusha T has come a long way from ripping up rhyme books. He signed his first record deal at 19 years old, and in the two decades since, he has seen dizzying highs and lows. We experienced some of the highs—the classic bars and critically acclaimed albums—along with him. But it’s the lows that helped him grow up: the end of Clipse, the group he formed with his brother, now better known as Malice, and the incarceration of some of his closest friends on drug conspiracy charges—a fate Pusha and his brother managed to avoid, despite, if you believe their lyrics, their apparent close ties to the operation. That was seven years ago. Today, Pusha is a grown-ass man, president of Kanye West’s record label G.O.O.D. Music, and a rap Hall of Famer with a renewed purpose: working with politicians (he campaigned heavily for Hillary Clinton), activists like Dream Hampton, and director Ava DuVernay to end the system of mass incarceration he narrowly escaped and shut down the pipeline that shuttles children of color from schools to prisons—particularly in his home state of Virginia.

“He’s one of the people willing to do the work,” says Hampton, who recently collaborated with Pusha on the #SchoolsNotPrisons Tour and a PSA against draconian drug laws. “If you look at his catalog, the War on Drugs and mass incarceration are issues he has talked about for a long time.”

I moved to Virginia Beach, Pusha’s hometown, when I was 6 years old; I was a teenager when Clipse blew up in 2002 with its Top 40 hit “Grindin’.” The beat—replicable with just a balled-up fist and a hard, flat surface—became the soundtrack to every lunch period across the country that year. I had a chance to see Pusha, however briefly, back in 2003, when he made a visit to my high school.

We were a new school, having opened up just two years before, and we needed to get accredited by passing Virginia’s Standards of Learning standardized tests. As an incentive, students were told Clipse and its producer/mentor Pharrell Williams would attend our homecoming pep rally if we performed well. We passed, and they did. It seemed like the entire student body banged out the “Grindin’” beat from the bleachers while Clipse took seats on the football field and waved. Ten minutes later, they were gone.

Pusha doesn’t seem impressed with the story, though he’s generous enough to say that he vaguely recalls the visit. It’s not that he’s not into my memories of a 10-minute school visit he did more than a decade ago; he’s just not into wasting time—or words.

The night before Pusha sat down for this interview, Drake dropped a new song, “Two Birds, One Stone,” that contains what are most likely shots aimed at him, continuing a thinly veiled beef that began between the two in 2011:

But really it’s you with all the

drug dealer stories

That’s gotta stop, though

You made a couple chops and

now you think you Chapo

If you ask me though, you ain’t

lining the trunk with kilos

You bagging weed watching

Pacino with all your niggas

The Internet’s rap pundits perked up when Drake’s OVO Sound Radio, on Beats 1, broadcast the song on October 24, the night of his 30th birthday. Pusha didn’t rush to record a response to Drake’s suspected subliminals; he’s more calculated these days. It’s also possible he was too busy. This fall, he hit the campaign trail with Clinton and her vice presidential nominee Tim Kaine, toured prisons, recorded both his next album and political PSAs, managed several businesses, and answered calls from his friends in federal prison, something he does every day.

When I tell Pusha I need to ask him about “last night,” there’s no need to elaborate. He drops his head, takes a peek at his fresh-out-of-the-box, white-on-white Raf Simons Adidas, chuckles, and replies, “You need that energy, man.” He laughs again. He’s not reacting—he looks like he’s plotting.

Or perhaps Pusha doesn’t have much to say about Drake’s seeming shots at his past because he has said so much on wax already. The story of his rise from drug dealer to world-famous rapper is now infamous. He repeats it anyway.

“For me and my friends, drugs was the mischief,” Pusha begins. “It’s what everybody did, it’s what kids did. You sold drugs. That’s what you were going to do.”

He doesn’t say this with any sense of pride or regret. He says it like it’s a fact, one that he’s only now starting to understand fully. “You didn’t make plans for that to be your occupation. It was just what you did, and it was easily accessible and in abundance.” And, if you’re looking to make money, it’s a lot more effective in the short term than music. “My friends weren’t into rapping. It was my brother and my select group of artistic buds. But outside of that, it wasn’t happening.”

Nonetheless, by the time Terrence was a teenager, he’d stopped tearing up Gene’s rhyme books and become captivated by his brother’s passion for music. Gene taught him that rap was more (and better) than MC Hammer, whom Terrence loved at the time. Terrence would skip school to hang out with Gene, his best friend Traci (also an MC), as well as Williams and Chad Hugo, a.k.a. the Neptunes.

“One day, we were all over at [Traci’s] house and I was like, ‘Man, I’ma write me a rap.’” Everyone liked it, and Williams came up with an idea: “Y’all should be a group!” Gene became Malice, Terrence became Terrar (and, eventually, Pusha T), and Clipse was born.

His origin story is well known, but Pusha, a natural and captivating storyteller, still makes it exciting. His signature braids whip around as he grows more animated describing road trips with Williams to go hear dope go-go records in D.C., and being inspired by the early Master P joints his friends brought back from the Jack the Rapper hip-hop conference.

Produced entirely by the Neptunes, Clipse’s first proper release, Lord Willin’, went gold. They went out on tour with Jay Z and 50 Cent, and even performed at the MTV VMAs with Justin Timberlake. All of this turned Pusha and Malice into superheroes for hip-hop fans back home. It also made them world-famous rap stars.

The music business, however, is far from kind. In 2004, a merger between Sony Music Entertainment and BMG forced the brothers to move from Arista to Jive, while Star Trak, the Neptunes’ imprint, moved to Interscope. The label reshuffling effectively put Clipse on hiatus until 2006, when it was finally able to release its critically acclaimed sophomore album, Hell Hath No Fury. In an industry, but especially a genre, where new stars push out the old before they even get a chance to burn, four years between releases can be a death sentence. Rap money isn’t guaranteed; drug money, on the other hand, is easily accessible and abundant. Pusha found himself, in his words, “double-dutching between rap and the streets.”

“Sales wasn’t cracking in 2006,” he says. “What do you think that was like? For three years?”

By the time Hell Hath No Fury was released, Clipse was already on its second label and heading to its third.

“My mindset was that I didn’t believe in music,” Pusha says.

The streets, on the other hand, were insurance against the fickle nature of the music industry. Until they weren’t.

In 2009, the duo’s manager, Anthony Gonzalez, was charged with operating a multimillion-dollar drug ring. A year later, he was sentenced to 32 years in federal prison. (When Pusha raps about “Tony” on songs like “40 Acres,” from My Name Is My Name, and “Blow,” from the Fear of God mixtape, he is referring to Gonzalez.) Several other of Pusha’s associates were also arrested; prosecutors said Gonzalez was at the head of an operation that distributed literal tons of marijuana, cocaine, and heroin throughout the Northeast. According to his 82-count indictment, Gonzalez laundered the proceeds through a number of legal businesses, including Soul Providers Management, Clipse’s booking agency.

“Everybody that I came into the music game with in ’97, and I’m talking about my friends that I was with every day, seven of them are locked up in jail,” Pusha says. “From 10 to 34 years now. First-time offenses for most of them.”

At the same time his friends were getting locked up, Terrence’s brother quit Clipse. Malice changed his name to No Malice, reconnected with his Christian faith, and disavowed rapping about drugs and violence. Rap was never Pusha’s dream, always his brother’s. Terrence started out shooting down that dream, tearing up the rhymes a teenage Gene held so dear, because he wouldn’t pay his younger brother enough attention. Terrence had a change of mind, followed in his brother’s footsteps, and got his wish; he could now spend every day with Gene. And then suddenly, that was over. Pusha T found himself alone and at a crossroads—double-dutching seemed more uncertain, and more dangerous, than ever. With the pressure on, Pusha chose music.

“I just dove in head first,” he says. In 2010, Pusha signed to West’s G.O.O.D. Music label after the two became close on West’s Glow in the Dark Tour. Pusha delivered two verses for My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, including “Runaway,” and then set off to define his solo sound via a string of mixtapes and an EP. My Name Is My Name, a full-length released in 2013, and King Push—Darkest Before Dawn: The Prelude, released two years later, can be described as the grim soundtrack to a dope boy’s nightmares. “Drug Dealers Anonymous” and “H.G.T.V.,” two 2016 releases, suggest that King Push, his upcoming third solo album, will deliver more in that vein. Whether West's recent battles with paranoia and depression will affect the album's release remains to be seen. The day after West checked himself into the UCLA Medical Center, Pusha commemorated the six-year anniversary of MBDTF with a post on Instagram, thanking West for the opportunity to contribute to the album. However, in a follow-up interview, Pusha tells me he hasn't spoken to West since his hospitalization, and declines to speculate on his condition.

In the meantime, as Pusha continues to refine his unmistakably ominous approach to coke rap, he’s also taking on an executive role with his work as president of G.O.O.D. Music, a position he was appointed to by West in November 2015. Proving he has an ear for what’s next, he signed 19-year-old Brooklyn rapper Desiigner, of the Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 “Panda.” You might be one of the people who’s mad at Pusha for that, one of the people who complains that Desiigner sounds too much like Future, or is just plain unintelligible. Pusha doesn’t care.

“My past is cemented.

My past happened.

Like slavery happened.”

“I don’t subscribe to anything or anybody who speaks ill of anybody on the label, especially Desiigner,” he says. Pusha’s been in this game for nearly 20 years, and he knows that in order to survive you can’t be resistant to change. “I want ground-breaking creativity,” he says, and he feels he has found that in Desiigner. “This is another moral obligation that I feel I need to bring to the game.”

His other moral obligation is speaking up about mass incarceration. After his journey—one he says he's lucky to have survived—it's personal. “It’s probably the single most [pressing] issue that I’ve seen affect my demographic, my people, my culture,” Pusha says. “I lived through it.”

A few years ago, Pusha got in touch with Hampton, who had already launched effective social justice campaigns with artists like Jay Z and John Legend. Hampton says Pusha was looking for a way to connect a song he was writing to a campaign to help recently-released prisoners reenter society. “He’s a smart guy; he studies,” Hampton says. “It was easy to bring him up to speed on what the movement was about.”

Through conversations with Hampton, President Obama, and DuVernay—whose documentary 13th, which investigates the connections between slavery and the prison-industrial complex, proved eye-opening for the rapper—Pusha began rethinking the “mischief” of his youth and the deeds outlined in his catalog. What he once accepted as just the way things are, what led to the incarceration of some of his closest associates, was part of a larger, more nefarious system.

In particular, the so-called schools-to-prison pipeline is victimizing a significant portion of today’s black and Hispanic youth, a fact that has changed Pusha’s understanding of our country’s inherently unjust justice system. His home state is especially culpable. In 2015, the Center for Public Integrity analyzed data collected by the U.S. Department of Education measuring the rate at which schools referred their “disorderly” or “misbehaving students” to law enforcement agencies. Its analysis showed that Virginia led the country with a referral rate almost three times the national rate. And of the students referred, more than a third were either black or Hispanic.

“When you get the knowledge that I’ve come across recently, it’s like, oh my god…,” he says. “You want to tell kids the truth.”

It’s this kind of advocacy that was sorely missing in his own life. Luck, he admits, saved him from becoming another man with a number for a name. But instead of letting the next generation play with fate, he wants to help them stay off the streets before it’s too late.

“When you’re 18, 19, jumping off the porch, you don’t consider the deck being stacked,” he says. And the more he understands, the more he feels “duped.”

“I don’t like feeling like I’ve been taken advantage of, like you’re preying on my lack of knowledge. Had I been looking at it from that perspective, I might not have made some of the choices [I made]. We might not have made those choices.”

And it’s the “we” that haunts Pusha. Because, after all, his talent provided him with options that his friends didn’t have and, while he could bring them along, he could only take them so far.

“I feel like I thrust people into an industry without….” His voice trails off. “Me as an artist, I’m the focal point. I brought in people who were my focal point. In the midst of me weaving between music and the streets, I can go out of town, go away, have something to do. But the same way I don’t depend on [music], they don’t depend on….”

He’d rather not dwell on his past too much. Pusha is about action. His concern for how mass incarceration has decimated black communities is the major reason he signed on to help elect Clinton as the next president of the United States.

Which, to anyone who is versed in the history of the criminal justice system, might be as controversial as Pusha’s decision to sign Desiigner. Clinton infamously supported the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, signed into law by then President Bill Clinton, which is largely credited with helping to explode the prison population during the ’90s. Mandatory minimums and three-strike laws helped lock up more black people for longer. However, for Pusha, Clinton’s willingness to apologize for supporting that bill, advocate for justice reform, and embrace someone like himself, with his past, speaks to the possibilities of building new coalitions to fix the broken system. “I do think she cares about mass incarceration,” he told Complex ahead of the election. “Now, why she cares versus why I care, that could be different. I don’t really have time to deal in that. I like the fact that we both care about something and, together, if we can fix it, that would be amazing.”

Clinton, of course, won't be the 45th President of the United States. She lost to Donald Trump, and Pusha witnessed the devastating defeat live from Clinton headquarters in New York City. I spoke with Pusha again three weeks after the election; he was, like the rest of us, still grappling with the results. "As the evening went on, you could feel the energy shift—we were extremely disheartened," he recalls. "I just thought it said so much about America. I just didn’t understand how he could speak so ill to so many different groups of people and they still find a way to support him. The [support from] white women was a bit much for me. I thought that said a lot. The blatant disrespect to that group in particular, over and over again throughout the campaign—the people who voted for him did not care. Trump is trying to extend the lifeline of and expand upon white privilege. The racism in America—it’s no longer hidden. They don't feel the need to hide anymore, because your president didn’t hide it in any capacity."

Not all of Pusha's efforts were thwarted on Election Day, though. That night, voters in California passed Proposition 64, a referendum to decriminalize recreational marijuana for which Pusha made a PSA. The measure's impact on the criminal justice system has been immediate, forcing prosecutors in Califonia to reduce charges in and completely dismiss some cases currently in the courts.

And despite the daunting prospect of Trump's promised "law and order" presidency, Pusha says he's undeterred from his goal of ending mass incarceration. "I’m going to continue to fight up until Inauguration Day, then we have to strategize a bit better with regard to how and what we’re going to do going forward," he says. "It’s truly going to be tough and everyone knows that. There has to be a new strategy because we’re not dealing with people who actually care about our people."

This is Pusha as a statesman, determined, magnanimous, and candid. Except maybe not when it comes to Drake.

“I heard something,” he says, simultaneously playful and dismissive, when I ask him again about “Two Birds, One Stone” and the Internet chatter that Drake’s lines were directed at Pusha, questioning the street bona fides of his past. “I would never, ever attribute that [song] to myself. My past is cemented. My past happened. Like slavery happened. The Holocaust happened. You can’t ever question anything that has actually happened.”

It’s not so much that his prowess as a drug dealer is being questioned by Drake, but that his very foundation may have been called a lie. To doubt Pusha’s story is to doubt who he is now. It’s those years that made him, for better and for worse, and it’s those years that inform how he moves through the world now, eager to learn, grow, and help end the oppression of our modern criminal justice system. It’s those years that give him the insight that makes his music resonate, that makes fans feel like he’s speaking directly to and for them.

So I ask him directly: Was Drake rapping about him or not?

“Listen,” he says. “I’m not speaking to him at all. I’m telling you, the real of it is: It ain’t real if it’s about me.”

Mychal Denzel Smith is a New York Times bestselling author of Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching, and Knobler Fellow at The Nation Institute.