Mariah Carey is, as usual, hiding in the open. Maneuvering through the main dining room at Nobu Malibu with a small entourage, she’s wearing large sunglasses and a leather jacket draped over her shoulders. Trailed by flashing camera bulbs and the dinner crowd’s murmurs, she sits with me at a barely-lit table on the restaurant’s outside deck, overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

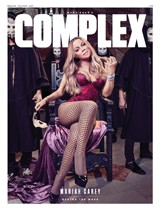

It’s a cool summer night, but the heat lamps radiate enough warmth that she discards the jacket, revealing, well, a lot—just not much in the way of clothes. There is a concise black skirt, an overwhelmed bra, and a wisp of a black top. Mostly, though, her look is all boobs and legs.

“I didn’t want to walk over without my jacket on,” she explains. “This ensemble’s a little see-through!”

Carey has made a career of divulging what she wants when she wants to—which isn’t often. After decades in the tabloid spotlight, she’s successfully walled off most of her life from the public. She’s notorious for canceling photo shoots and turning down interviews. A colossal financial success and a diva par excellence, Carey has riches that mere mortals simply can’t relate to—and an origin story to match. “I don’t have a birthday,” she jokes when asked about turning 46 in March. “I was just dropped here. It was a fairyland experience.”

So in many ways, Carey’s upcoming E! show, Mariah’s World, an eight-part docuseries slated for the fall, is a surprise. It promises the requisite look inside the celebrity bubble, including rehearsals for her European tour, the planning of her wedding to billionaire James Packer later this year, and her unrelenting campaign against unflattering fluorescent lighting. But it won’t be, according to Carey, a put-it-all-out-there show in the style of the Kardashian clan—who are, coincidentally, filming something in a private dining room 15 yards away.

“Some of us,” Carey says, casting a glance toward the room, “talk about other people and what they do and la la la. But I’m not that person.”

Still, Carey’s combination of glamour, curves, and shade, expertly delivered, should make Mariah’s World perfect reality TV. And that’s what some people are afraid of. Tabloids have quoted “insiders” worried that a reality show will prove embarrassing for her. Wendy Williams railed against the idea, citing Whitney Houston’s regrettable appearances in Bravo’s 2005 series Being Bobby Brown. Director Lee Daniels, whom Carey has been close to since they filmed Precious, went on SiriusXM to voice concern that verged on spilling tea.

“She is very fragile, and she has been through a lot,” Daniels said. “She has been used, she has been abused…. Some people don’t have that Teflon sort of thing that I do, so she masks it with this coquettish thing that is hiding her nervousness and her pain and her own family’s abuse to her. She is misunderstood.”

Days after Daniels’ lament, Carey posted his inevitable mea culpa to her IG and Twitter feeds. The subtext, though, was a clear admonition to all other critics of Mariah’s World. She’s been famous since she was 20 years old, when her self-titled debut exploded onto the charts in 1990. After 26 years in the spotlight, two divorces, a “breakdown,” and a “comeback,” all roadmapped by 18 No. 1 hits, concerns about her opening up in a public forum are dumb. After all this time, do you really think Mariah Carey doesn’t know her best angle?

How do you want it...how do you feel?

Carey is singing 2Pac. Specifically, she’s launched into K-Ci and JoJo’s hook on the rapper’s 1996 hit “How Do U Want It” as a means of explaining that, over a career in which she’s collaborated with Jay Z, Snoop, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Nas, the LOX, Rick Ross, and Jeezy, the MC she most regrets not having worked with is 2Pac.

Livin’ in the fast lane, I’m for reeeeeal...

“If I would’ve had a song like that?” she wonders. “C’mon—I live for that!”

Her exuberant rendition is a reminder that Carey’s frequent ventures into hip-hop helped shatter the pop princess bubble decades ago. Her 1995 “Fantasy” remix with Ol’ Dirty Bastard was a landmark record that paved the way for the rap/pop collaborations that still proliferate the charts. Back then, she fought for the ODB feature and won a concession from her label, Sony, whose execs saw it as an appropriative move rather than an acknowledgement that Carey was part of the culture. “They were like, ‘Oh, she’s interested in this little rap music,’” she remembers. “I was like, ‘No, I’ve grown up on this. You think it’s something new. You’re kidding me!’”

In hip-hop, Carey found the perfect foil for her hyper-perfect vocal runs. “I love the grimiest rappers in the world,” she says. “That’s my favorite.” Carey remembers driving around New York one night listening to Mobb Deep’s “Shook Ones” when she got the idea for “The Roof,” an album cut from 1997’s Butterfly about fleeting romance. She was similarly inspired in 2002, when she heard Cam’ron’s “Oh Boy” and flipped the beat for her single “Boy (I Need You).” Carey flew Killa to the island of Capri to record; he returned the hospitality by giving her a guided tour of Harlem in his Lamborghini. When she pointed out landmarks that even he didn’t know existed, Cam realized she was just as comfortable uptown as he was.

Carey found that through her hip-hop collaborations she could flex as both the moll and the boss, navigating between the two impulses to do whatever she wanted. People remember her vamping on roller skates in the “Fantasy” video, but few remember that it was also her directorial debut—she rigged a camera to a roller coaster a decade before GoPros were invented. (Twenty years later, she’s still behind the camera: In May, she signed a three-picture deal to direct, executive produce, and star in original movies for the Hallmark Channel.) She’s hammed it up in roles as a gangster’s perennial arm candy (she was a high-maintenance drug courier in State Property 2 and the only girl in the “Roc Boys” video, for instance). But IRL, when renowned record exec L.A. Reid first took over at Universal in 2002, he asked Carey for advice on who should fill the president’s seat at subsidiary label Def Jam. Carey suggested her friend Jay Z—who just so happened to be waiting outside Reid’s office. “A lot of rappers don’t have to go through what I had to go through as a singer,” Carey says. “I was always in a bubble that they put me in, but I was always punching out. It was a tough line to walk.”

Pop diva is the most familiar veneer to Carey’s onlookers. One could roughly sketch the arc of her career just by describing what she wore at each major point: black bodycon dress (from the artwork for her eponymous debut album), Santa-red snow suit (from “All I Want for Christmas Is You”), Bond girl bikini (from “Honey”), diaphanous gold gown (from The Emancipation of Mimi).

But now that Carey’s fully embraced her hard-earned legacy-act phase (she launched a Las Vegas residency, #1 to Infinity, last year), its emblematic moments—the Mimi memes—have not all been flattering. There was the contentious American Idol run in 2013 that pitted Carey against Nicki Minaj in a weekly ego-off. Then, a year later, her disastrously off-pitch isolated vocals from a 2014 Rockefeller Center Christmas special somehow leaked after she’d reportedly been late to the show and held up production.

Since then, she’s been increasingly willing to make fun of her flaws, purposefully playing up her diva image to let you know she’s in on the joke. In April, she reportedly threw a Mariah Carey-themed party in Italy where guests dressed up in their favorite looks of hers. In June, she deigned to be interviewed by Jimmy Kimmel while both sat, fully clothed, in a bubble bath. The gag was a clear nod to her 2002 Cribs episode, MTV’s highest rated, which saw her mount a stair climber in stilettos and show off an entire screening room inspired by The Little Mermaid.

Carey’s self-effacing winks at her reputation will continue with Mariah’s World, though she says she had to warm up to reality TV’s unscripted format. “I’ve become more comfortable with it. In the beginning I was like, ‘Fine, we can document the tour, we can show what’s happening behind the scenes, with the singers, the dancers, the this, the that. You can see me when I’m on stage, I’ll talk—blah blah blah.’ But what I started to realize is that my best moments are off the cuff.”

Her most revealing, too. Long before my plan to fumble out a question about her still unresolved divorce from Nick Cannon, Carey asks if I’ve got kids (her twins, Moroccan and Monroe, turned 5 in April). Before I finish gagging on my Pinot Grigio, she offers, “I never thought I would either, but I never thought I would have babies with someone and then get divorced. Like, ‘Oh, great job. Repeat your past.’”

“But life happens,” she continues, waving her diamond-encrusted butterfly ring, “and it was supposed to happen. It’s fine. For [my children], I wish it hadn’t happened that way. For me, it was...[singing Johnny Mathis and Deniece Williams’ “Too Much, Too Little, Too Late”] Guess it’s over. Call it a day.” Carey says she wasn’t initially looking for a new love—until her friend, filmmaker Brett Ratner, introduced her to “a regular, normal person”: Packer, who proposed in January with a 35-carat diamond ring after less than a year of dating. They bond over a shared sense of humor, Carey says, and don’t let their busy, jetsetting schedules get in the way. “I don’t expect him to be at every little thing that I do, and vice versa. He’s got a lot of stuff on his plate and so do I. There’s a mutual understanding.”

Carey laughs when I describe their wedding as a “merger” and ask if bringing two successful moguls together is difficult. “We would like for it not to be a big thing, but the reality is it has to be,” she says. “Because there’s things that are specifically mine, and he’s got huge friggin’ conglomerate stuff and I’m not looking to take that from him. So it has to be dealt with. Anytime you get married to somebody [it does]—and I should know. This’ll be marriage number three. My bishop said to me, ‘I don’t want you to go Elizabeth Taylor on me!’ I said, ‘I’m not’—and then I said ‘Bye.’”

Carey won’t disclose much else about her relationship with Packer: “He’s a private businessman and there are a lot of things with his companies that I just can’t talk about. It’s just not good for me to do.”

But she does reveal that he’s long been obsessed with her music, and listens to different Mariah playlists while he travels. The fact that he was a huge fan didn’t scare her off. “Actually, if he didn’t like my music, then how would I be able to handle him being around when all I’m doing is creating?” she muses. “It’s cool.”

Music is the organizing principle, and starting point of reference, for pretty much everything Carey does. Threads of songs—hers, everyone else’s—weave their way into everyday conversation. “That’s our way to communicate,” Big Jim Wright, Carey’s longtime collaborator and the musical director of her Vegas run, tells Complex over the phone. During the course of my 45-minute conversation with Carey, she sings bits of at least nine different songs. Flawlessly. Without ever calling me dahhhling.

Most of Carey’s career has been about finding ways to grab the mic on her own terms. Even as she was promoting the docuseries and gearing up for more Vegas dates, Carey quietly began work in the final week of May on the 14th studio album of her career. Last year she signed a multi-album deal with Epic, a division of her original label home Sony, that will re-team her with L.A. Reid, who oversaw the release of her 2005 comeback The Emancipation of Mimi when both were at Universal. “I love Mariah; I consider her my ‘musical wife,’” Reid says. “We’ve been working together for nearly 15 years, and it was very important to me to bring her back home to Sony. Mariah started her career here. I wanted to bring the family back together again.”

The deal returns Carey to the label that discovered her under vastly different terms than when she left in 2000, two years after divorcing its then-chairman, Tommy Mottola. “The fact that a lot of my catalog is on Sony is important to me,” she says. “I had to leave when I did because there was no way I was staying there.”

It is well-trod history that Carey’s 1993 marriage to Mottola—her first, his second—cast him as svengali and her as caged bird (she used to call their mansion “Sing Sing”), and that their animus bled over into the business. In his 2013 autobiography, Hitmaker: The Man and His Music, he described his relationship with a young Carey, who’s nearly 20 years his junior, as “absolutely wrong and inappropriate.” Michael Jackson, during his infamous rant about Sony in 2002, disclosed some unsavory details Carey told him about Mottola: “‘Michael, this man follows me,’ she said. He taps her phones.” Both Jackson and Carey struggled to release new music under Mottola’s watch.

Their battles weren’t just about release dates, but about creative control over their music, Carey says. “If Michael Jackson were alive he could sing, [The Weeknd’s] ‘Can’t Feel My Face.’ He could sing any of those songs. And sometimes it reminds me, ‘Oh, I wish that Michael would’ve had a song like this’—I loved when he did [the 2001 song] ‘Butterflies’ and songs like that. They would always hate on that at Sony because they wanted him to do these big pop records.” By and large, labels aren’t interested in pop superstars proclaiming their independence. The Weeknd famously rejected songs Swedish superproducer Max Martin wrote for him. Martin eventually opened up to collaborating on the writing, which birthed the Weeknd’s No. 1 pop breakthrough “Can’t Feel My Face.” It stands to reason that if Carey were interested only in sales, she has the budget and the talent to call in A-list producers and songwriters for a by-the-numbers, ready-made hit. But Carey has written much of her own canon. That’s often misconstrued as meaning that she only pens lyrics. “We create the bed of music that I’m going to sing over [together],” she says. “People don’t really get what that means unless you do it. They think, ‘OK, so she probably writes the lyrics.’ No, I write the lyrics, the melody, and the music with [producers]. I’m not a piano player—I can play a little bit—but I really like to help mold whoever’s playing.”

During the recording session for “Mine Again,” an Emancipation-era torch song with ’70s horns and vibes, producer James Poyser found out that even when Carey lets her guard down, she’s still in control. The song was the first collaboration between the two, and Poyser, the keyboardist for the Roots who has also produced songs for D’Angelo, Erykah Badu, and Jill Scott, among others, didn’t know what to expect from their first session and meeting, arranged by American Idol judge Randy Jackson.

“You never know what somebody is like. Are you gonna get along? Is it gonna be a cool experience? Is it gonna be weird? There’s a lot of weird, uncool artists in the music industry,” Poyser says. “I was sitting in the studio for a while and then there was a bustle of activity. You could just feel a whirlwind enter the room—I’m like, ‘Oh boy, here it comes.’ And then she comes into the room with me and is absolutely the coolest person. She says, ‘Hi,’ pulls up a chair right next to me, and we start writing. It was almost like she knew exactly what the song was gonna be instantly. Like, she knew what she wanted and in a way grabbed my hand and walked me toward it. That’s the thing that stuck with me. You could see that she knew.”

Carey hasn’t forgotten how hard it’s been to acquire and maintain creative control as she navigates the current landscape of surprise album drops and Apple Music- and Tidal-only releases. 2016 stars like Beyoncé, Drake, and Chance the Rapper seemingly have more freedom than Carey and Jackson did back in the day to create without an exec breathing down their necks—and a more direct way to profit from their work. “I’m lucky that I got into this in the 1990s,” Carey says, “because I was able to [singing Rihanna] work work work work work. Tons of albums. That was all good, but I’ve noticed a total difference in how you make money now.”

When Forbes named her the sixth-richest woman in entertainment in 2007, with an estimated net worth of $325 million, the magazine cited Carey’s income from selling over 200 million albums and publishing royalties derived from music she’d mostly written herself. In 2015, when her estimated $27 million in revenue ranked ninth on Forbes’ top-earning women in music list, it was based on income from the Vegas residency and endorsement deals like her Game of War commercial. Her video for that year’s single, “Infinity,” features heavy match.com placement. Odds are that Mariah’s World will be mentioned in her inclusion on Forbes’ 2016 rankings.

But Carey’s biggest inspiration for pushing back at the major-label system isn’t a new-millennium star. “Prince was one of the best people I’ve met,” Carey says. “He didn’t care about the big system. I was always like, at any time Prince could write a No. 1 song, because he’s that talented, but he chooses to do what he wants. I respect that. He actually helped me through a lot of situations with his knowledge. He always had a plan. I just can’t believe he’s gone. I was hoping that it was a trick that he was pulling—that it didn’t really happen.”

Prince mastered image maintenance, which, for him, meant preserving a little mystery about himself. But Carey says she learned the art of public seduction—teasing out some private info, burying other bits—from Marilyn Monroe, her biggest inspiration and the namesake of her daughter. At age 5, Monroe is a year younger than Carey was when she walked in on her mom watching Gentlemen Prefer Blondes just as “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” the Technicolor title song and dance scene that Marilyn Monroe is best remembered for, began. Carey says she showed her toddler the same scene; Monroe looked up and asked to watch the whole movie from the beginning. “She’s 5. She doesn’t know what they’re saying—it’s from the 1950s—but she’s been walking in my heels since she was 2,” Carey says.

In the Internet age, Marilyn Monroe’s legacy is often reduced to thotty Instagram memes. She’s a froth of hair and makeup, jewels and cleavage, layered under misattributed quotes. But that’s not how Carey sees her. It’s an oft-recited fact that the singer owns Monroe’s white piano, a prized possession for both. It was reportedly the first thing that the actress’ mother bought for their first house when Marilyn was a child. Her mom painted it white and set it in the middle of their empty living room. But I’d never heard Carey explain its significance. While her publicist shoots me the first of three wrap-it-up glares, I scramble to ask the one question I’ve always wondered about her Marilyn standom: As a multimillionaire fan she could conceivably own any number of Monroe artifacts—so why the piano?

“That was the only thing that she had from her childhood. I haven’t touched it—I won’t even tune it,” Carey says. “I could’ve bought the dress, the [sings] Mr. President dress. But I’d rather maintain what she cared about.”

She looks me square in the eye. “You know that her production company was the first female-owned production company in Hollywood? She paved the way for women in a lot of ways that a lot of people don’t think about. She was so ‘the sex symbol’ that it looks like the opposite, but she really wasn’t that.”

On that note, Mariah Carey—sex symbol for sure, but also singer, composer, director, entrepreneur, and mother—gets up, leaving behind a half-finished cocktail. Swaddled once again in her jacket and eyebrow-to-cheek covering shades, she teeters in high heels on Nobu’s wooden planked deck, her careful steps assisted by a ponytailed assistant. It’s not the sips slowing Carey down, though—it’s the skintight, there-but-not-there ensemble. She only wants to show just enough.