As rapper/producers and true multi-instrumentalists, Ty Dolla Sign and Mac Miller represent both a kind of kitchen-sink avant garde and the sort of old-school chops that are getting increasingly difficult to come by. In addition to the samplers and DAWs that have become standard fare in the hip-hop world, both can play piano, guitar, drums, and bass, and both see their wide skillsets as vital to their success. Growing up on opposite sides of the country, using different regional and stylistic influences to craft their sounds, both Ty and Miller found inspiration by writing and recording using electric guitar, bass, and organ as often as possible.

While Ty was still in elementary school, his father enjoyed some success as a member of Lakeside, a west coast funk group best remembered for the 1980 classic "Fantastic Voyage." While Ty's father was in the group, the song was enjoying an enormous resurgence as a result of its use in Coolio's 1994 hit of the same name. With Dr. Dre firing on all cylinders, classic funk samples were forming the bedrock of west coast hip-hop, and from his bedroom in South Central Ty was being exposed to two generations of classics. "I'm listening to a Snoop song," says Ty, "and Pop shows me, 'Oh, that's George Clinton'."

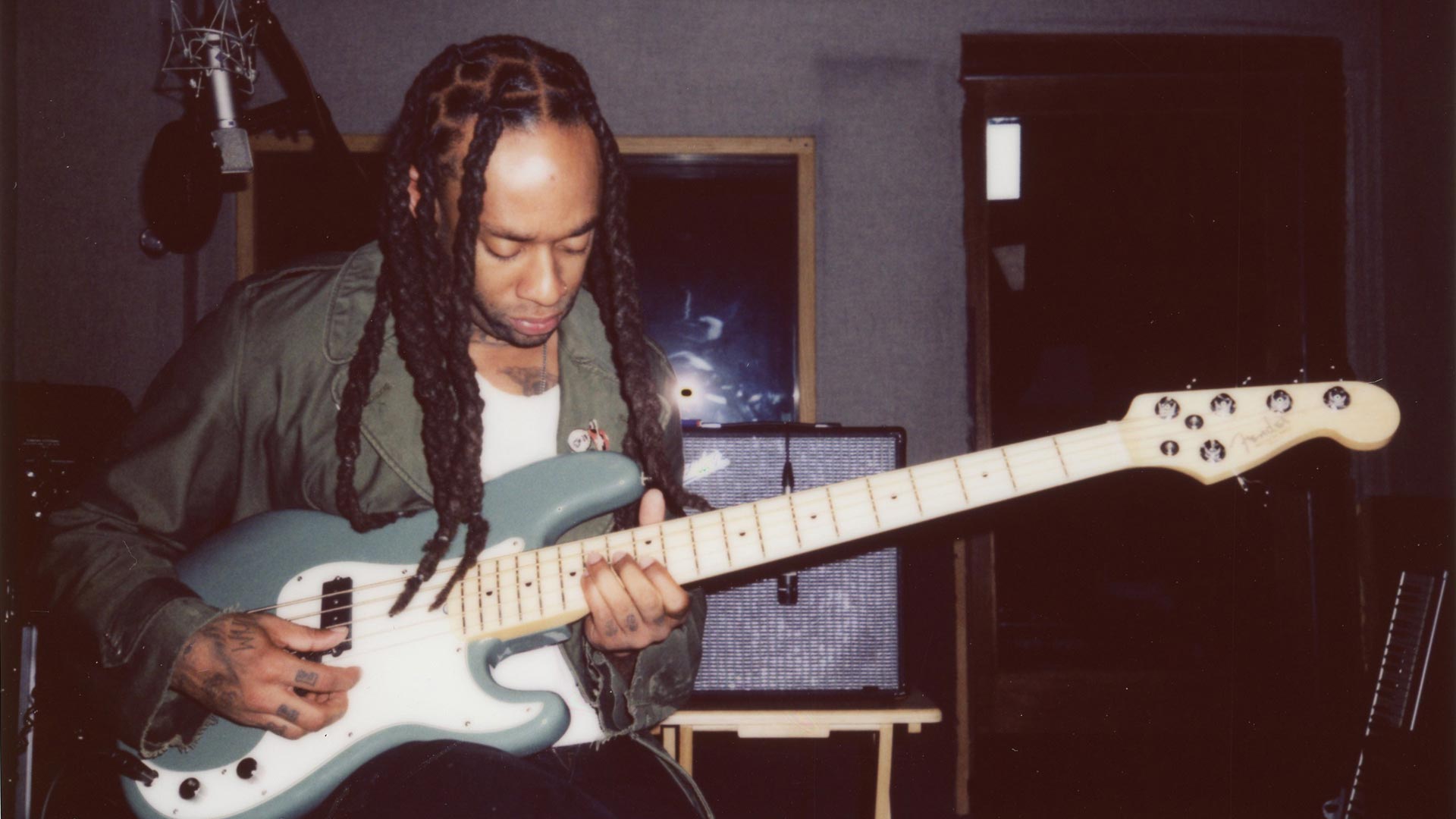

It was only a matter of time before Ty's fascination with G-funk's roots and the instruments his father had lying around the house began to cross-pollinate. "When I first picked up my dad's [bass]," he says, "I couldn't figure it out for real. So I [tuned each one] to the note I wanted it to go to, and I played a bass line." After a bit of course correction by his father, Ty quickly became an expert, writing his own music and even amassing an instrument collection of his own. "The P-Bass, the Jazz Bass, those are my two favorites," says Ty, adding, "P-Bass, that's the classic Motown [sound. It] makes a great R&B record. If I'm onstage and I want you to really hear what I'm doing, it's the Jazz Bass. It's just two different moods."

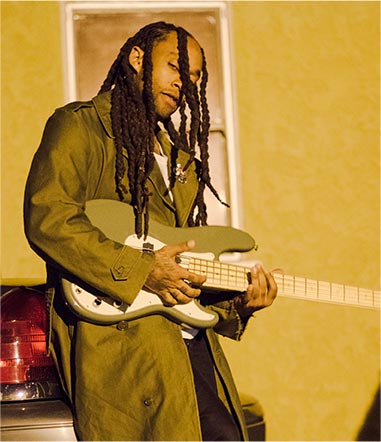

The ability to access these different types of moods, to be able to either step outside the world of digital sampling or work alongside it, is central to why Ty and Mac keep these guitars and organs by their sides. "I got started making music when I met this kid back in the day— He showed me how to make a loop using cassette tapes," says Ty, before adding: "Real Rhodes, real organ, real bass— real everything. It's all about the real shit." It's not so much about a guitar's perceived authenticity as it is about the ability to keep one's options open— to be able to compliment sample-based beatmaking with live instruments, and vice versa.

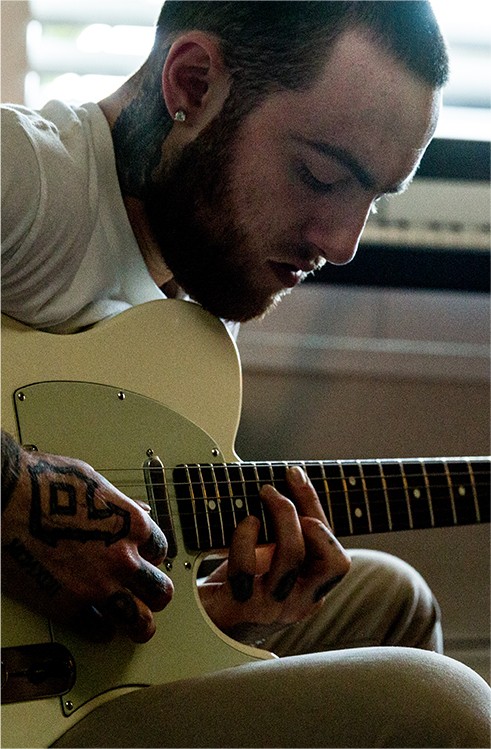

Miller, too, finds a certain level of freedom in playing guitar that he can't access otherwise. Describing his guitar's ability to tap into a stream-of-consciousness sort of creative flow, he says, "To [keep] the wheels of inspiration turning and create from scratch, you've got to give yourself time. Just play for the sake of it."

In terms of hip-hop legacy, turn of the millennium-era Pittsburgh is—to put it bluntly—not as well-known as early-nineties Los Angeles. Nevertheless, Mac Miller came up in the Point Breeze neighborhood taking musical production seriously from a young age; he taught himself guitar, bass, drums, and piano, and began focusing on musical production above all else before he finished high school. Listening to Miller talk and play, it's clear that making music has taken on an extremely natural place in his life. "It sounds like water," says Miller. "Like the ocean, like floating. That's [what] my guitar sounds like and feels like to me."

The pick-up-and-play nature of a guitar is central to the way Miller expresses himself through his creative work. Where using an electronic setup can require forethought, fine-tuning, and a big-picture sense of what's being worked on, Miller says, "I don't like to plan much. I like to hit record, see what happens, and figure it out later."

Indulging that impulsivity is central to both Miller's creative process and, it seems, to him as a person. It's about creating something that expresses things that Miller couldn't put into words or, occasionally, things he didn't even know in the first place. "It's nice to not have to talk to describe how you're feeling," he says. "It's nice to learn about yourself by sitting down, picking up a guitar and playing." For both Miller and Ty, the barrier of entry to playing a guitar is so low—you sit down, you pick up a guitar, and strum—that the act can quickly move ahead of mechanical or intellectual concerns and into a more purely creative mode, a mode that allows for different types of results than slowly but surely building a beat on a sampler.

One of music's greatest and most celebrated qualities—whether it's being listened to, written, or performed—is the ease with which it can take people who experience it beyond language. "I've seen people who can really play," he says, "who can speak better through their instrument than they can in conversation." The more easily the hurdles of physical mastery (or lack thereof) can be overcome, the more easily this level of expression can be accessed.

At the same time, however, it's not as though Miller's finished products take the form of a slapdash, improvised jam. Artists like Lauryn Hill and the Beastie Boys have long been counted among his influences— artists who are famous for using live instrumentation to aid in crafting expansive, complex studio projects. The man has an A Tribe Called Quest tattoo. For Miller, the reason to use live instruments on his records is simple: it allows him an outlet for aspects of his personality that might not have anywhere to go otherwise. "I have to expose some part of myself that I'm uncomfortable with," he says.

Both Ty Dolla Sign and Mac Miller have spent the better part of their lives making themselves comfortable with the kind of creative process that only a real guitar, keyboard, or bass can provide. While the initial investment required to learn an instrument may seem high, Ty notes that the dividends are there as well, saying that playing and recording on his bass "always delivers." And while it seems more important than ever to have a specialization, a brand or lane that can set an artist apart from the pack, casting a wide creative net helps artists like Ty and Miller be the dynamic and versatile producers and rappers they are. To hear Ty tell it, it sounds like common sense: "The best of the best are using [live instruments]."

These artists' commitment to using and playing live instruments allow them to mine veins of inspiration that might have otherwise remained hidden. This impulse— to leave no stone unturned and find inspiration in as many sources as possible, to dedicate yourself wholly to your craft so the expression created by your art can be as undiluted as possible— is the mark of a student as much as an artist, and when it comes to learning or creating, neither Ty nor Miller seems particularly interested in slowing down. Ty summarizes it well: "Anybody can use the laptop, but do you know where these sounds come from?"