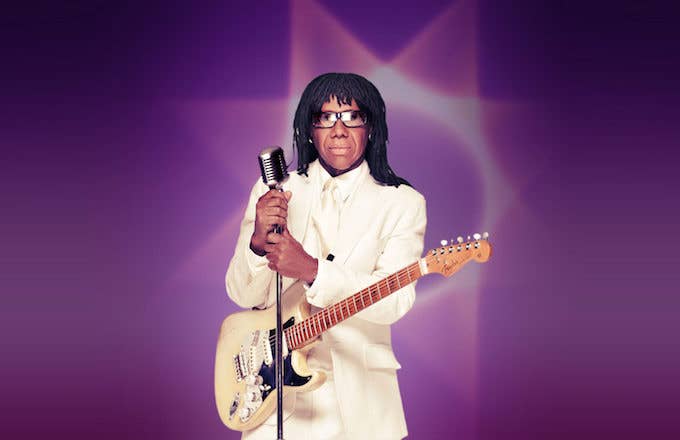

Nile Rodgers needs no introduction. The guitarist, songwriter, producer, and composer played as big a role as anyone in shaping the sound of popular music over the past 40-plus years. As a member of Chic, he wrote iconic songs like "Le Freak," "Everybody Dance," and "Good Times"—the last of which formed the basis for the first hit rap song, "Rapper's Delight."

As if that wasn't enough, he and his Chic bandmate, the late Bernard Edwards, co-wrote and co-produced the 1979 Sister Sledge album We Are Family, the title track of which was recently selected for preservation in the Library of Congress. Nile also produced David Bowie's best-selling album, Let's Dance; produced and co-wrote (with Edwards) Diana Ross' 1980 solo album diana, including its smash hit "I'm Coming Out"; and produced Madonna's 1984 breakthrough Like a Virgin. There was also iconic work with INXS, Duran Duran, Debbie Harry, Mick Jagger, and pretty much everyone else. Oh yeah: and he's worked on the soundtracks to films like Coming to America and Beverly Hills Cop III.

In 2013, Rodgers returned to the spotlight alongside Daft Punk. The robots added Rodgers' inimitable style to a handful of songs on their album Random Access Memories, including a little ditty called "Get Lucky"—maybe you've heard of it?

But in addition to his musical endeavors, Nile is involved in charitable ones as well. Friday night marks the annual gala for his We Are Family Foundation, an organization founded in the wake of 9/11 that "creates and supports programs that promote cultural diversity while nurturing the vision, talents and ideas of young people who are positively changing the world." The honorees this year are LL Cool J, Roger Daltrey of the Who, and several survivors of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas shooting: students Morgan Williams, Jack Macleod, Ariana Ali, and Sarah Chadwick; and heroic teacher Melissa Falkowski, who hid 19 students in a closet during the massacre.

Complex got Nile on the phone a few days in advance of the gala to talk about the celebration, his incredible career, and what we can look forward to on the next Chic album.

What’s going on with the We Are Family foundation right now?

We’re helping to sustain a lot of really smart, fantastic teams. We have three main initiatives. We have TEDxTeen, which is huge. We have Three Dot Dash, which is our flagship project. We bring kids from all around the world for a week of media training, a week of sustainability training, a week of storytelling, and it’s incredible. These kids have affected a billion people in just ten years. From the time that we’ve started, we’ve done things as vast as building schools in places as far away as Nepal and Nicaragua and Malawi and Mali.

You have your annual gala coming up this week. There’s a huge musical component. But in addition to that, you are honoring some teens and a teacher who survived the Parkland shooting. Why have them at the gala?

When we started this organization, we knew that at some point in time, the teens would basically take it over. We’ve already hired former GTLs, Global Teen Leaders. We have two now that sit on the board. Almost all of the kids that are nominated every year are nominated from past participants.

Specifically, it happened that we got the kids from Parkland because of the visibility of our organization. They reach out to us and vice versa because we have a two-way dialogue with teens now. We have created that platform where the teens know that we amplify their messages.

For the musical part of the gathering, you’re honoring LL Cool J and Roger Daltrey. Any surprises in store for their sets that you can share?

Then it wouldn't be a surprise, would it? We would just be telling you, oh, guess what they’re gonna do.

The musical part of our gala is always really fun, but we always want it to be different. So with LL, we’re trying to do a battle between my band Chic and the DJ, which I think is gonna be brilliant. It’s rare that I get to play other people’s music unless I’m doing a gala or something like that. So this is going to be fun, to play music that I love and grew up with, and Roger Daltrey is a super gentleman. Oh my god, he’s such a nice guy.

The foundation is named after one of your songs, "We Are Family." What do you think it is about that song that’s been so enduring?

I have no idea. If as a composer you could know those types of things, you would do that every time. You just write from your heart and there’s something I call convergence that I look upon as these elemental forces outside of me that have to do with my work connecting to people. I just try and do the best I can every time. Every time I make a record, I try and make a No. 1 record. Forces outside of me make it that No. 1 record. I don’t have anything to do with that part after I finish. I’m like okay, there it goes.

There’s a pretty famous story about Chic writing "Freak Out." The original title was "Fuck Off," because you were mad at getting turned away at the door of Studio 54. Are there any other famous songs of yours that have R-rated scratch titles?

No, not really. That was just a moment in time. We were just starting out. The club was brand new, the hottest place in the world, one block away from my apartment. We were invited by Grace Jones. I mean, come on. Everything was supposed to be perfect and we were supposed to impress her with our promptness, our professionalism and the whole bit. None of that happened, so we just went and bought two bottles of Dom Perignon—which we used to call rock n’ roll mouthwash at the time—and we downed those two bottles and started singing, "Oh fuck off. Fuck Studio 54." And that wasn’t even an original lyric, because that’s what the doorman told us to do. It wasn’t like we thought of it. It was like, he said it. Okay, we'll turn it into a song.

I'm in New York City, and a lot of people here have been thinking about David Bowie again because of the Brooklyn Museum exhibit about him. What's something about Bowie that people would be surprised to know?

So much has been exposed about him. Everybody knows that he's a terrific painter. Maybe the most humanitarian, meaning the most human being, the least racist person I've ever met.

Oh, I know what what most people don't think of [about] Bowie: that he's a fanatical jazz lover, to the point where it's off the charts. I mean, he loved avant-garde jazz and very, very deep stuff. Not the normal stuff that one would consume—although he would like that too. The reason he and I wound up working together is because when we first met, we started talking about [avant-garde jazz pianist and composer] Cecil Taylor and people like that. I mean, that's way off the beaten path.

Back in 1979 or so, a bunch of bands started replaying one of your songs, "Good Times," and having people talk instead of sing over it. What did you think at the time? Did you understand what was happening?

Well, everything happened so fast. The very first time I was exposed to it, Debbie Harry and Chris Stein from Blondie took me to what they called a hip hop. When they took me to a hip hop, the only record they seemed to play was "Good Times." There was a procession of MCs that rhymed to "Good Times." It was the only song. They had two turntables and two copies of "Good Times," and they would just stand in line and everybody had a verse.

It was amazing to me. I was like, wow, what is this? It was like people painting graffiti art—you don’t know how long it’s gonna last, but it seemed really exciting at the time, like when you first saw people voguing or something. Then the next thing you know, I was at a nightclub talking to a good friend of mine, and a record came on that was that same format—basically, "Good Times" with a whole bunch of people rhyming over it.

I was like "Woah, what’s that?" I went over and I looked at the label and it didn't have my name on it. I was like, wait a second, you can't do that. And they took the strings directly from my record. It was the beginning of sampling. [Rodgers and Bernard Edwards ended up suing Sugar Hill Records for copyright infringement, and the resulting settlement gave them songwriting credit on "Rapper’s Delight."]

I went over and I looked at the label [of "Rapper's Delight"] and it didn't have my name on it. I was like, wait a second, you can't do that.

There have been some reports in the press lately about the new Chic album. What can you tell us? I know some names have leaked out about possible collaborations.

Ever since I moved into Abbey Road [Studios, in London], every artist that’s in town seems to pop by. When they do, we work together. We just put in a full day’s work, and it’s been coming out amazing.

There are reports that Bruno Mars was involved in the new album. What was it like collaborating with him?

What happened was I was actually working with Anderson .Paak, who was opening for Bruno Mars during their U.K. tour. So Bruno came down to the studio and got on the piano and started playing something and we were like, "Wow, that’s actually pretty great." [Laughs]. I didn't finish that song yet, but it's really great. The only reason why I wouldn't finish it right at this second is because I have to make it fit the narrative [of the album]. I have to get the lyric right to make it make sense.

We just had a funny day. We were talking about Prince and all of our different experiences with him. Then I played some wacky jazz chords and Bruno Mars said to me, "Hey Nile, that’s a funny chord you got at the beginning of that song." I didn’t quite understand what he meant, so I said, "What do you mean by funny?" And he says, "Well, funny if you want a hit," and then we all just started cracking up.

It was just such a fun session. I'd like to keep that vibe, but because we were just playing for hours and hours, I hadn't focused on it because at that point, I was so clearly focused on what the album was at that point in time.

You were very close with Avicii. Because of his passing, a lot of people are now talking about his struggles. But I wanted your perspective on something a little happier: what he was like to work with, and what made him a star in the first place.

He was one of my favorite people in the world to work with. I mean, we never had a bad word or anything like that. I told him that's impossible. When you're making music, it's about conflict, right? You have an idea, the other person has an idea and you say, "Well, wait a minute, what do we change?"

Whenever he and I did that, it always seemed to make the music better, and it was always just natural. And I know the reason why: because Avicii is such a great natural melody writer that he can write himself out of any corner. So if I came up with some wacky jazz chord changes or progression, he would write some beautiful thing to tie it together. We would say, you know, why did you put a Lydian scale over that? He’d look at us and go, "What?" And we’d go, oh right, he has no musical training. He’d say, "I don’t know man, it just sounds cool," and he’d be right. Honestly, maybe one of the best, if not the best I’ve ever worked with.

Avicii is such a great natural melody writer that he can write himself out of any corner. if I came up with some wacky jazz chord changes, he would write some beautiful thing to tie it together.

That is high praise given your catalog.

Yeah, no kidding. I worked with a lot of them, and it just came out of him. And he was a step editor, which is really interesting. It’s not like he would sit down at a piano and play some beautiful melody. He would make the melody one note at a time.

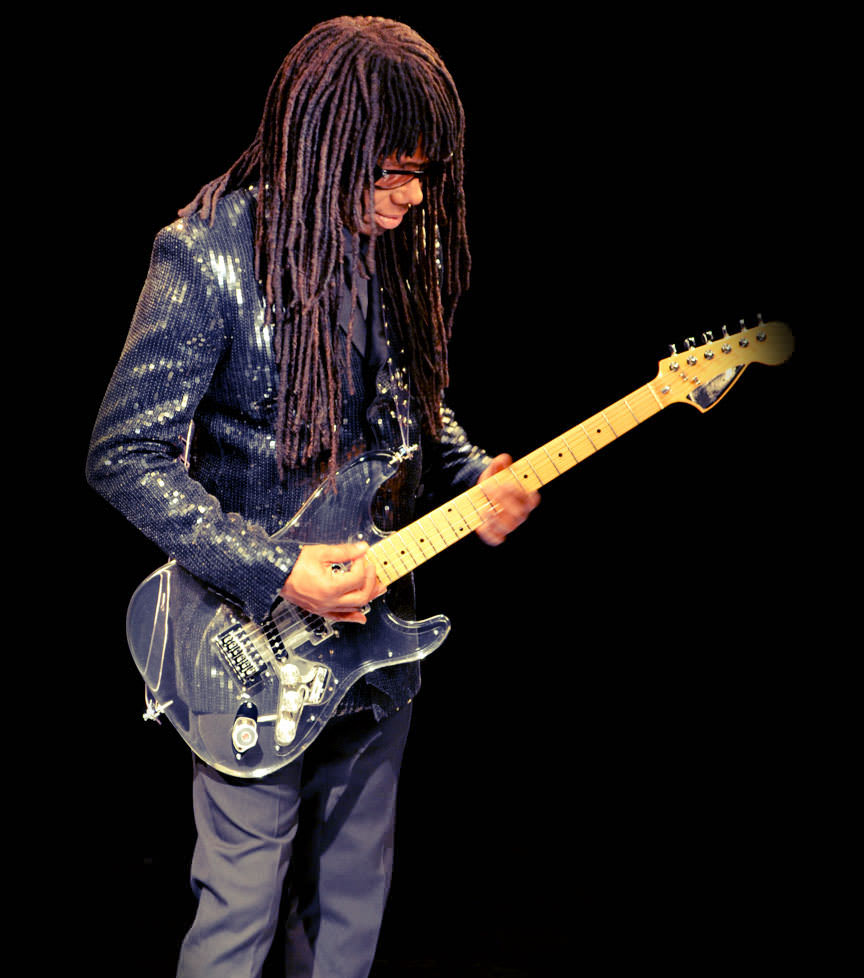

You came up in an era when live instrumentation was pre-eminent. At least in the pop field, that's becoming less and less the rule over time. What does having live players on a song bring that’s different than programming?

For me, it's the give and take. It's the interplay between the live musicians. I've heard interviews with my musicians and they explain it really well. They say, Nile will write out a rudimentary chart. I don't have to have it exact unless there’s a certain spot in the song where we must all play together and do accents. But basically, it's groove-based stuff, and we’re trying to get through the arrangement. They're not that crazy because I want to have the looseness of the performers having a good time. When you program music, you are making it exactly the way you want it to be, and there's a big difference in my heart and my spirit when it comes to real-time performance. Every Chic show is totally different because it’s a real-time performance.

I don't think people realize—and in a way, I don't think they care, as long as they're getting a show—but when you see most acts in today's world, what you’re getting, especially from the music and even a lot of the singing, is playback. You're getting something that's already happened. Whereas when you see a band like Chic, you're experiencing what we're experiencing in real time, and that sounds different. Something that's already happened and captured and fixed and altered and terrific and wonderful, that's gonna sound like that every night you play it because it’s already done and it's fixed to a clock and it's made perfect and it's in tune and all that. But that's not a real-time event. That's something that's happened. That's history. You're playing history back. But when we play, we're actually playing in the here and now.