“Shit, it’s my job. We all got a job.”

Jim Jones is downplaying my flattery-disguised-as-an-interview-question: What’s kept you going in the music business for two solid decades, since your appearance on Cam’ron’s “Me, My Moms & Jimmy” back in 1998?

Upon first hearing Joseph Guillermo Jones II on that track, few rap fans would have pictured that the guy setting up My Two Dads punchlines would become arguably the most relevant and successful member of one of the genre’s most influential crews. Not bad for someone who, by his own admission, initially planned on just “playing the back.”

Jones was introduced to the hip-hop business early—at around age six, actually, when he met his neighbor Dame Dash. And right around that time, the legend of one of Dame’s future Roc-A-Fella co-founders was spreading.

Kareem “Biggs” Burke was known to a young Jones as “one of the bosses” of their Harlem world.

“[Biggs] has always been around Harlem, been around the East Side. Always been a little older than me, been known for hustling, for having some money, for having a weapon,” Jones recalls. Even now, he talks about Biggs’ brother, the late Robert “Bobalob” Burke, in similar awed tones (“He used to be in Harlem with all the cars… Bob had pretty girls and stuff like that. Every drug dealer’s dream.”) In addition, Jones went to school with another one of Biggs’ siblings, Kyambo “Hip Hop” Joshua, who himself would go on to play a key role in the Roc on the A&R side.

At 13, Jones met the person who would go on to shape his musical life: Cameron Giles. Without realizing it, the future Capo had stepped into a milieu that would set the tone of Harlem rap for the next few generations. Jones’ new pal Cam was part of a group of neighborhood kids who used to play basketball and hang out together. They called themselves the BBO Crew (it stood for, among other things, “Bending Bitches Over”). One of their members was a kid named Mason Betha, who Jones remembers being an entertainer even as a young teen.

“That's what Mase used to do; a lot of dancing,” Jones says. “He used to have this crybaby dance he used to do, where he looked like a baby crying on the dance floor, shit like that. Like, ‘Give ’em the baby, give ’em the baby,’ he'd start crying in the middle of the dance floor. Mase has always been an entertainer.”

Clark Kent was one of the first people to tell me, ‘Don’t let anybody trick you out of your position... We all get better at what we do.’ He was one of the first people to give me that inspiration.”

Out of that scene came a rap group, Children of the Corn, which was originally comprised of Killa Cam, Murder Mase, Darrell “Digga” Branch, and Cam’s cousin Derek “Bloodshed” Armstead. Fellow Harlemite Lamont “Big L” Coleman would join a little bit down the line. Jones was around the group in their high school days, but wasn’t yet rapping. Bloodshed, who died in a car crash in 1997, was perhaps the hungriest of the bunch, and a teenage Jones loved to hear him rap.

“I remember I used to pay Bloodshed a quarter for him to do freestyles. [I’d] give him $3 before the day was done,” Jim remembers. “God bless his soul. Blood was a special, special person.”

By the mid-1990s, the CoC crew had their first role models. Two Harlem rappers of their generation were starting to make their mark in the music business. Herb McGruff appeared on singer Monifah’s 1996 song “I Miss You (Come Back Home)” alongside rap vet Heavy D. “That put [McGruff] on a different planet in Harlem,” Jones says wistfully. And then there was Big L, who signed to Columbia Records and dropped his debut album in 1995.

L was a part of the CoC family, but in addition got hooked up with the Bronx crew Diggin’ in the Crates. Coleman’s success—and his style—provided inspiration to his fellow Harlemites. Even now, coming up on two decades after L’s tragic murder, Jones remembers that the late rapper “always had the latest leather jackets.”

But even with the success of his peers, Jones wasn’t yet inspired to make music himself. It wasn’t until Bloodshed died in March of 1997 that the idea of rapping became something Jones took seriously. It was then that Mase began showing Jones how to write and record. And even though Jones admits that he was “a little bit terrible” when he first started out, he had some important and early supporters.

“Clark Kent was one of the first people to tell me, ‘Don’t let anybody trick you out of your position. You said some things in your music that wowed me, so practice your craft. We all get better at what we do,’” he says, still proud at the memory. “He was one of the first people to give me that inspiration.”

During this period, Jones was inseparable from Cam, shepherding his friend’s rap career, which was beginning to take off. Cam caught the ear of Biggie, who was on the verge of signing Cam to Undeas Recordings, the label Big launched with Lance “Un” Rivera. In the wake of Big’s murder in March 1997, it was Jones who made sure that Un followed through on his late pal’s promise.

“Cam and his mom had owned a liquor store,” Jones recalls. “We had just come back—I think it was Saturday, we closed early. They were shooting the ‘We’ll Always Love Big Poppa’ video in Harlem. We got outta the cab, walked through on Morrison [Avenue], and I was tellin' Cam, ‘That's Un, that's Big's partner right there.’ He was like, ‘Fuck that. We gotta take a chance.’”

Jones talked to Un and explained the situation, and Cam’s first record deal, with Epic and Rivera’s Untertainment, followed. In short order, so did Jones’ first appearance on record—the aforementioned “Me, My Moms & Jimmy.”

Jones’ behind-the-scenes smarts were showing even on that early record. While it’s Cam’s mother who raps on the track alongside Cam and his pal, it was Jones who came up with the hook, inspired by a song that his mother used to love, Junior’s 1982 hit “Mama Used to Say.”

“That was one of my mom's favorite songs. I was like, ‘We gotta do that sample, if we gonna do a song with your moms,’” Jones remembers of his initial foray into A&R.

After two albums on Epic (1998’s Confessions of Fire and 2000’s S.D.E.), Cam realized he wasn’t getting the money he wanted out of the Sony building. Un, simultaneously, was losing footing at the label. Enter Jones’ childhood pal Dame Dash, who started managing Cam, which led unsurprisingly to a deal at Roc-A-Fella. And from there, with his 2002 LP Come Home With Me, Cameron Giles’ star status finally began to match up to his talent. But while his friend was becoming “a very big star,” Jones was trying to manage all of the opportunities that came along with that.

Although Jones wasn’t signed to Roc-A-Fella himself, he remained an integral part of Cam’s career—overseeing business opportunities, finding new talent, and still making time to rap on two Come Home With Me tracks. “It was a little confusing at times, when you got so many things coming at you at once,” he remembers of those heady days. “And we never had the proper set up of people around us.”

When people see you're getting ready to be in a powerful position, they take you for a joke… ’til they find out it's serious. I don't think people expected me to do no music or rapping or anything like that. So I understand why they'd take it a joke.

Whatever the confusions and lost chances, the Roc deal allowed Cam to get Jones’ first major discovery, an eccentric spitter named Juelz Santana, into the rap game. Jones met Santana (who he says is still his favorite rapper) when Juelz was still a teenager. While the youngster’s vocabulary and metaphors wowed Jones, it was Santana’s attitude that sealed the deal.

“His confidence was one of the biggest things that I noticed; he never put his head down, not once, when he was rapping,” Jones remembers of that first encounter. “He rapped like he was talking, and he was comfortable in doing that.”

Following Cam’s success, the Diplomats stepped into the spotlight. The crew, consisting initially of Cam, Jones, Juelz, and Cam’s cousin Ezekiel “Freekey Zekey” Giles, would evolve to add members, second-tier affiliates, European chapters, and even comedian Katt Williams to the mix.

The crew released their albums not on Roc-A-Fella, but instead teamed up their burgeoning Diplomat Records label with Koch Records. Koch G.M. Alan Grunblatt, a man who had helped acts as varied as Fat Joe, Common, and Three 6 Mafia break through during his long career, became so enamored with Jones that Grunblatt eventually made Jones the label’s Vice President of Urban A&R.

The Dips’ first two albums would become iconic, and position them as the kings of early-aughts NYC rap. But even with Jim playing a key part in the group as their self-described “Capo,” the idea of Jim Jones as a rapper was still strange to many. It wasn’t until the crew, and Roc-A-Fella itself, began to fall apart in the mid-2000s that Jones took the reigns of his own artistic career. His early attempts to do that were met with skepticism, even from industry folks like Irv Gotti who Jones had known for years.

“When people see you're getting ready to be in a powerful position and aspire to be something successful, they take you for a joke… ’til they find out it's serious,” Jones says. “I don't think people expected me to do no music or rapping or anything like that. So I understand why they'd take it a joke.”

In the end, no one was laughing. Jim Jones, the man beside Cam’ron almost every moment during the entire back half of the 1990s, finally released his debut solo album On My Way to Church in 2004. It was, of all things, his oft-proclaimed Blood affiliations that really set it off.

“Certified Gangstas,” a tribute to N.W.A.’s “Boyz-n-the-Hood,” only made it to number 80 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart, but it, well, certified Jones’ place in the rap world. The video featured the debut of the Game—much to his label’s dismay, as they had planned a more standard rollout of their new artist. Also appearing in the video was Eazy-E’s son Lil Eazy-E. And the fact that Jim Jones, a Blood from New York, appeared in a video repping West Coast gang culture surprised a whole lot of people.

“Even to this day, it still breaks barriers, that music that I did in that period in time,” he says. “We got so many people over here on the East Coast that's all in tune with people on the West Coast now. You got buddies from the East to the West, you got Crips friends with Bloods from the East Coast. I had a heavy influence.”

That success set the stage for later hits like “Pop Champagne” and “We Fly High.” The latter, with its classic “Ballin’!” ad-lib, was a smash hit, reaching No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100 in early 2007, and remained on the charts for half a year in total. The song’s video spawned a viral dance, and even Jay Z got in on the action, dropping a remix of the song in an unsuccessful move to best Jones, who had by that point been throwing verbal jabs in Jay’s direction for years.

Jones’ newfound commercial success allowed him the freedom to discover more artists, the way he had with Juelz Santana. And he did, playing an instrumental part in the careers of Max B and the late Stack Bundles.

The mention of Bundles’ name even now brings a tear to Jones’ eye. “A great spirit.” “One of the best dudes I ever met in my life.” “He’d give you the shirt off his back.” “A man’s man.” Jones’ praises for the murdered Far Rock rapper seem endless. As for his talent? “I still say, to this day, that Drake woulda had a problem on his hands. A big problem.”

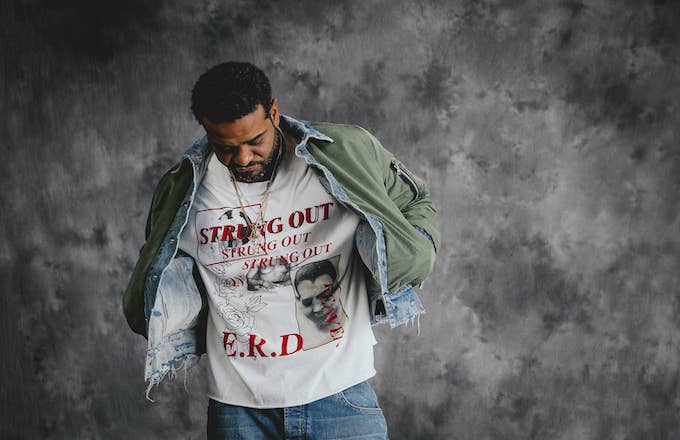

Jones has managed to leverage his rap career into a low-key mogul-dom as diverse as any Forbes-listed Diddy or Birdman. Today, many of his projects, both business and musical, are branded with the “Vampire Life” name. There are “Vamps”—crews of affiliated artists—in Atlanta, Miami, Boston, and Oakland, and plans to put out albums and compilations with all of them. There’s his new Latin artist Macotea. (“The Latin market, it's humongous,” Jones laughs. “Maybe it'll help me to speak fluent in Spanish.”) He still has his ear to the ground in Harlem, nonchalantly dropping names of soon-to-blow acts. “I keep a crew of young guys around; they keep me in the loop,” he continues, modestly. “They keep me relevant to what's goin' on. Uncle Jim can't go outside every day like he used to.” There’s his planned mobile phone service. His part-ownership of an arena football team. And, of course, a new album of his own, Wasted Talent, which is out April 13.

But despite all that has changed since the days of BBO, Jim Jones remains very much the same person he was back when he was first hearing wild tales of the street dudes on his block. The Harlem kid who still likes ice cream and Frosted Flakes served together has survived the odds and remained on top. In the end, Jones attributes his success to his work ethic.

“Working Baskin-Robbins, working in the music industry, no different,” he explains. “Gotta get up every day to get yours.”