In the dimly lit bar area of Ace of Diamonds, a strip club in West Hollywood—not to be confused with the considerably more famous King of Diamonds, the strip club in Miami that gave us Blac Chyna—a bartender, nearly naked from the waist down, mutters a mantra to herself, preparing. The occasion is Lil Pump’s 17th birthday. Because he’s still a minor, Pump’s record label, Tha Lights Global (with planning help from his major label distributor Warner Bros.), has rented out Ace of Diamonds the way you might rent out a bowling alley or a McDonald’s PlayPlace. A giant, wooden banquet table has been hauled into the bar area; seated around the table are publicists, marketing partners, and a pair of kids who look as if they’ve won a fan contest.

There are more strippers than guests. A slightly taller, much more regal table is placed perpendicularly at our table’s head. In the middle of that second table is a throne, upholstered in white embossed leather and with gold framing. It’s empty for now.

A wait staff materializes and works quickly, doling out lemon-pepper wings and mashed potatoes and prime rib. The open bar is curiously underwhelmed. Then, finally: Pump. He comes with a modest entourage (including the excellent Los Angeles rapper Desto Dubb, who likely has at least a decade on the guest of honor), wearing a blue cardigan with tiger faces all over it, open wide enough to show the Gucci logo tattooed on his sternum. He still has braces. Various handlers march Pump around the room for handshakes and muttered hellos. His dreads keep falling into his line of sight. As far as I can tell, he doesn’t eat.

A few minutes or maybe an hour later—time dilates a bit when everyone at the table is trying to Instagram one diner—that same wait staff brings out a white cake with a single candle on top, and the room breaks into “Happy Birthday.” By the time the cake is set down in front of Pump, it’s clear that it’s meant to look like a Xanax. (This is unlike the green Xanax cake that Pump used to mark his reaching one million Instagram followers.) All the adults in the room think this is very funny, but there are very few teenagers around to laugh. He blows out the candle and cuts the cake. Beside me, a Warner executive, who in context looks like Al Bundy, gushes about how Pump is “a rockstar,” then abruptly stands and says to the table, “Well, I’m out of here—can’t have fun when the boss is around.”

From there we move to the actual club area, which those of us attending can’t fully populate. People mostly crowd around to watch the stage show, while a couple of publicists sit on an overstuffed leather couch like chaperones, passing out one dollar bills like arcade tokens. No one buys a lap dance, instead preferring to photograph Pump as he receives them. At one point he frantically pushes a pile of money off his lap, fishing around for a plastic cup. The dancers themselves, apparently paid well in advance, take turns sweeping the cash into a neat pile in the corner of the club, which they then leave unattended—a nice Marxist twist on the whole thing. The house DJ keeps interrupting Migos songs to remind those of us in attendance that the “Lil Pump album coming soon!” as if every single person who can hear him isn’t working for Lil Pump right now.

I don’t know any more about Lil Pump than you do. I know that he comes from Miami, but really hails directly from the internet. He was born Gazzy Garcia in the summer of 2000 and, over the last 12 months, has become one of the most hysterically hyped rap artists in the country, at least among the demographic of rap fans that makes executives salivate. He frequently culls his SoundCloud page; as of this writing, only ten uploaded songs remain. The stragglers have three or four million plays, while his marquee songs—”D Rose,” “Boss,” “Molly”—each have upwards of 30 million. “Gucci Gang,” which he released after his birthday party, is already closing in on 20 million.

When I say I don’t know Lil Pump, what I mean is this: look back at that video, archived on YouTube, of the green Xanax cake. This is what Lil Pump does on the internet. He stands, bare-chested and exuberant, stumbling and slurring, punctuating every sentence fragment with “Bitch!” or his signature ESSKEETIT! This is the same persona that bears out in his music, more or less.

But that’s not how Lil Pump is in person, at least around Warner Bros. executives and 24-year-old writers. Over the course of my time with Pump (time around Pump, really), I’m warned by a publicist and two other members of Pump’s team that he can be standoffish during interviews; one person tells me this is simply a phase he’s going through, and that it makes him feel “empowered.” By the end of my time reporting this story, I found this to be a cynical view held by the adults in his life. Pump’s virtually impossible to interview. Nervous and monosyllabic, his eyes that appear slanted and bloodshot on Instagram turn kind, quiet, and skittish in direct contact. But there’s no aloofness or edge to him. In these settings he seems, simply and starkly, like a very shy 17-year-old.

The contrast, of course, is with those ten SoundCloud uploads for which Warner spent so much money. The contingent of young rappers who made their names together on SoundCloud this year—Pump, XXXTentacion, Wifisfuneral, Ski Mask the Slump God, and Pump’s close friend Smokepurpp among them—have several things in common: they’re all young, from South Florida, prefer lo-fi aesthetics and heavy distortion, and lift liberally from the minimalist freeform of early-2010s Chief Keef and Lil B. Their youth and raw energy (and perhaps most of all, their raw numbers) quickly made them an easy sell to major labels and to rap fans nationally, if not to radio.

It’s not difficult to see why Pump has been singled out, even among his promising peers, as a Great Mainstream Hope. Aside from being one of the youngest in the coterie, he’s got a clear, dynamic voice that is easy to imagine transposed onto more market-tested beats. In other words: whether or not the sound of 2017 South Florida SoundCloud fully breaks through to the mainstream, you can picture Pump crafting hit songs on his own. It also doesn’t hurt that he has a distinctive look, is racially ambiguous, and has 3.3 million followers on Instagram.

But his work is also still in its formative stages, beholden to his influences to a degree that occasionally overwhelms songs. His peers often sound as if they arrived at their shared aesthetic after much fishing and experimenting: take for example XXX, whose catalog contains stray shards that sound as if they were made much further up the Atlantic coast. Pump, on the other hand, is finding a voice on the fly. “D Rose” is appropriately dreamlike, but the beat does most of the heavy lifting, with Pump’s vocals punching in left and right and feeling around for a pocket that never quite reveals itself to him.

At one point, I ask Pump which rappers had a serious impact on him. The first answer comes quick: “Sosa.”

“Do you have a favorite Keef song?”

A beat, with what seems like sincere consideration.

“Not really.”

Pump’s self-titled debut, out last week, is lean enough to be agile. It’s not weighed down by scene-setting or autobiography. It runs just over half an hour with most songs clocking out before the three-minute mark. There are low points, though (see: “Foreign”) where this leaves the songs feeling like unfinished sketches, pale and indistinguishable from one another. And while it might be beside the point to critique his writing too sharply, Lil Pump can get dully repetitive, oscillating from joyless sex to nonspecific cars to money and Xanax and back again. The allusions to hustling are ripped from B-movies, the flows track closely with flows from Keef and Takeoff and Rich the Kid, etc. In a perfect world, this is what Pump makes as he refines his style and gets ready to set out on his own. When Sosa himself shows up, on “Whitney,” he deploys a starkly technical approach, pushing his emphasis back and forth across each bar. Pump gasps to keep up.

It’s possible I’m missing the point. Few popular musicians traffic as aggressively and exclusively in youth—maybe this is tremendous fun for people born after 9/11, and the frequencies are out of my ears’ range, like a dog whistle. The 2 Chainz collab is a delirious joy and Smokepurpp grounds his songs in a way that makes them feel vital, superfluous Rick Ross cameo aside. But as far as I can tell, Lil Pump is a collection of form exercises and genre experiments, yanked from the incubator and formatted to fit your screen.

At his best (let’s say “At the Door”), Pump skews a little quieter, a little grimmer. It’s sort of strange to hear him so self-possessed. The appeal of “D Rose”—and that of his Instagram—is that he’s a kid in designer clothes careening through adolescence under a haze of mild tranquilizers. “At the Door” is poised and only a little laconic, the sort of song that someone who lives in the studio stumbles onto. Very little of Lil Pump feels this finely crafted, although some of the more chaotic moments work on their own terms. “Boss,” from the SoundCloud-only days, is his best manipulation of tone, an extended sneer that’s his most endearing mode. Next, “Flex Like Ouu,” is a frustrating counterpoint, like an actor giving flat line readings to memorize a script. The goal might be the practiced monotone of Future or 21 Savage; the result is something like a demo.

Lil Pump will likely do impressive numbers. Right now, he’s projected to hit the top 5 on the Billboard charts, with the potential to hit #1. With much of the music economy moved not just online but now to measurable streaming platforms, the challenge for labels is distinguishing signal from noise. Clicks themselves are agnostic. Pump does have a sizable, sometimes cultish following, fluent in the knowingly goofy hyperbole that’s become how we talk about new, internet-native rappers.

His durability as a commercial force of any sort will probably come down to his ability to thrive outside of the scene that birthed him—that is, outside of SoundCloud’s friendly confines, but also outside of his early aesthetics. Scenes like South Florida’s often splinter and evolve in interesting ways, but seldom become bankable in any long-term sense for major labels. With that in mind, it’s promising that songs like “Iced Out” and “At the Door” succeed in the wild. “Gucci Gang” is an interesting mutation of Pump’s early attempts, a little more emotive, a little more flesh on the bone.

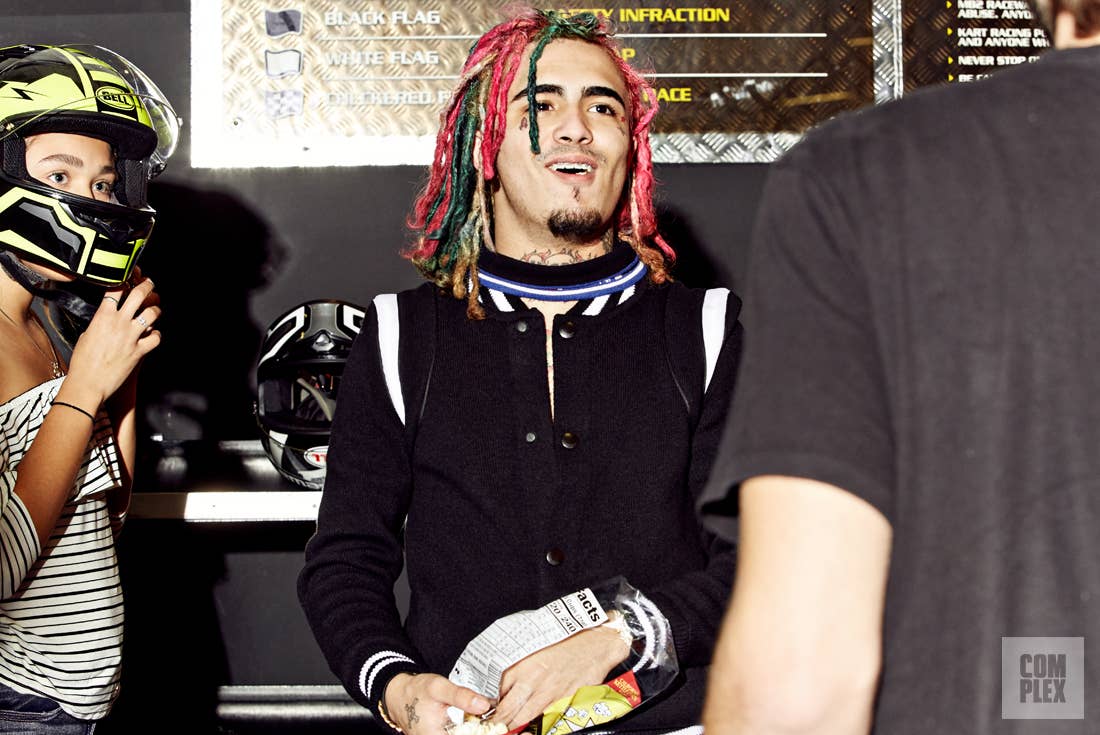

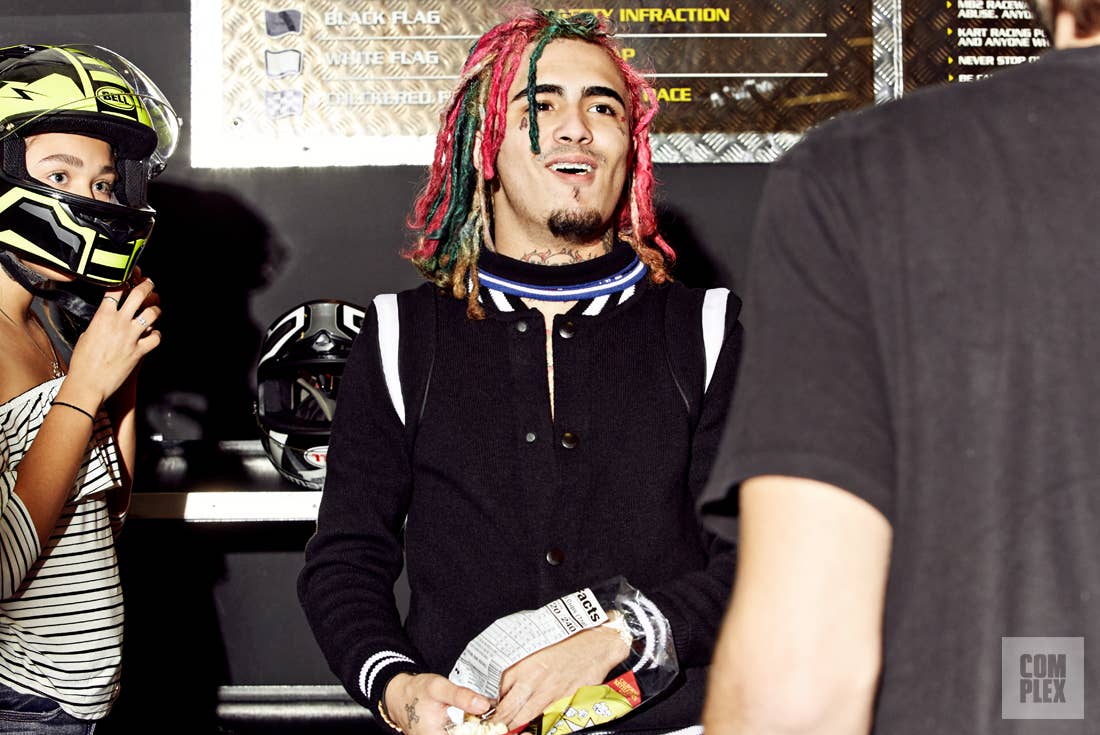

A few weeks after the birthday party, Lil Pump and I are deep in the San Fernando Valley, at a go-kart track. I should specify, for clarity’s sake, that this is not a strip club called The Go-Kart Track, but rather an airplane hangar-like building where people actually race cars over a too-slick cement track and where there are framed, heavily sponsored racing outfits, including one with an embroidered bottle of A1 sauce where the fly should be. Pump is accompanied by a handful of friends, security guards, managers, and publicists, who warn the photographers that he might prefer not to be photographed, being so standoffish and all. (Later, he’ll gamely pose, but not make eye contact with the camera, for the pictures you see on your computer screen.)

After a brief safety demonstration by a girl who promises that only one person has ever lost a finger here, we file out, eight at a time, to find our cars (karts, I guess). Your right foot controls the gas while the left hovers over the break; there’s also a tiny lever to throw the car into reverse, which is right next to a flourescent red emergency kill switch. Each race consists of about 15 laps, and because the cars are let out in careful intervals one at a time—for safety purposes—it’s not immediately clear who’s won. But when we’ve all pulled off the track and received comically detailed printouts of race data, it’s revealed that Pump, whose Givenchy jacket already looks like something a cultured French Formula One driver might wear on his day off, has quite literally lapped the field, having driven the fastest lap by more than a second.

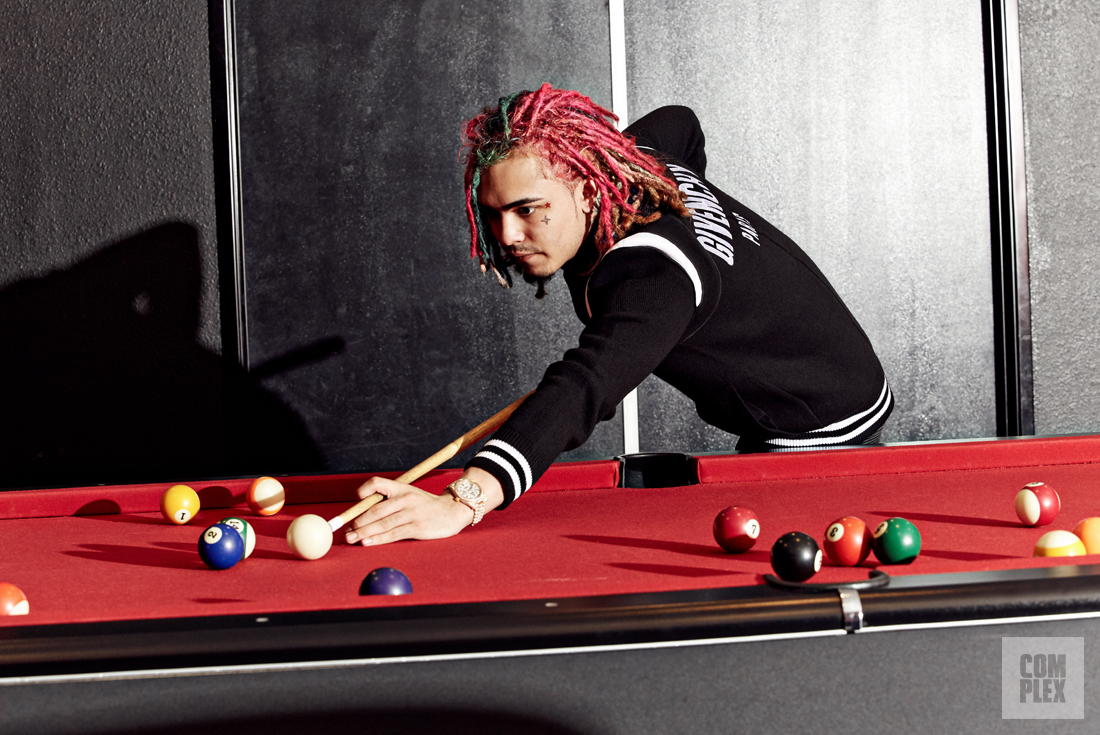

Between races, we retreat to a NASCAR-themed green room, complete with a pool table and an XBox that’s been pre-booted to a role-playing game of some sort that nobody seems interested in. Pump’s manager asks if there’s a liquor store in walking distance, which the go-kart track employee sheepishly explains is a question you shouldn’t ask a go-kart track employee before your second scheduled race.

The second race goes much as the first did: Pump wins in a landslide, this time deftly avoiding a three-car (-kart) pileup that almost turns grotesque. When he takes off his helmet and the little lice-repellant caps they give everyone, letting his hair fall back down to its natural state, he looks closest to the Lil Pump you see in archived videos: bounding around, ecstatic.

From there we all move to the arcade area. This is one of those places where you earn tickets that you can exchange for prizes, in this case inflatable dolphins of various colors, inflatable bottles of Tapatio, and a game of Operation. Pump, still wired from the race, shouts—this is the first and only time I’ve heard him speak much above a whisper—”it’s hot as shit in here!” and takes off his shirt, before carefully replacing the Givenchy jacket.

He and the CEO of Tha Lights Global, Dooney Battle, play each other in the pop-a-shot; Dooney’s clearly a much better shot, and if they were playing on a real court, could spot Pump eight points and beat him to 10, but Pump adjusts to the bizarro physics of carnival games faster and comes out with the W. Then Pump slides over to a motorcycle racing game, where he’s pitted against a waiting female friend. As the countdown starts on the screen, Pump pushes his hair back, then leans in like a real motorcyclist. Pump races like an Olympic runner who knows he has a great finishing kick: conservatively, hanging off the back of the lead pack. He earns a “power boost” that would allow him to pop a wheelie, which he ignores. On the third of three laps, he makes his move, climbing all the way up to second, before taking a turn too tight and crashing into the fence. He’s allowed to respawn, and eventually finishes sixth—a place that’s announced by the real, video image of a boxing ring-card girl, who’s made to look ghoulish next to the cartoon riders bikers to whom she’s miming congratulations.

Pump hops off the bike, and is immediately approached by a pair of teenaged boys who politely ask if he’d like to join their next go-kart race. He politely declines. I ask him if that kind of thing happens a lot.

“Yeah.”

“Does it make you wary of going out in public?”

At that moment, the girl who had warned of us possible severed fingers asks if Pump would take a picture with another employee, who can barely contain her excitement. He obliges, of course, and when the younger girl sees the photo on her iPhone, she leaps off the ground in joy.

There are other things I want to ask Pump about: Miami (“It’s nice”), the hurricane (“It wasn’t too bad”), SoundCloud (“It’s where I first dropped music”). But before too long, he and his friends are heading back toward their cars, eventually to the 210 and Los Angeles proper. But first Dooney finds me, and explains that this might be the most access a publication ever gets to Pump, that he’d like to keep one publication as his outlet to the world, “like Jay does with Rap Radar.” While we’re talking, Pump and his friends are lingering in a parked car, crammed together, mugging for a front-facing camera. Members of his team flock toward me, asking if I got what I needed, politely apologizing for the lack of a longer interview. He’ll open up more in the future, they promise. It’ll be different.