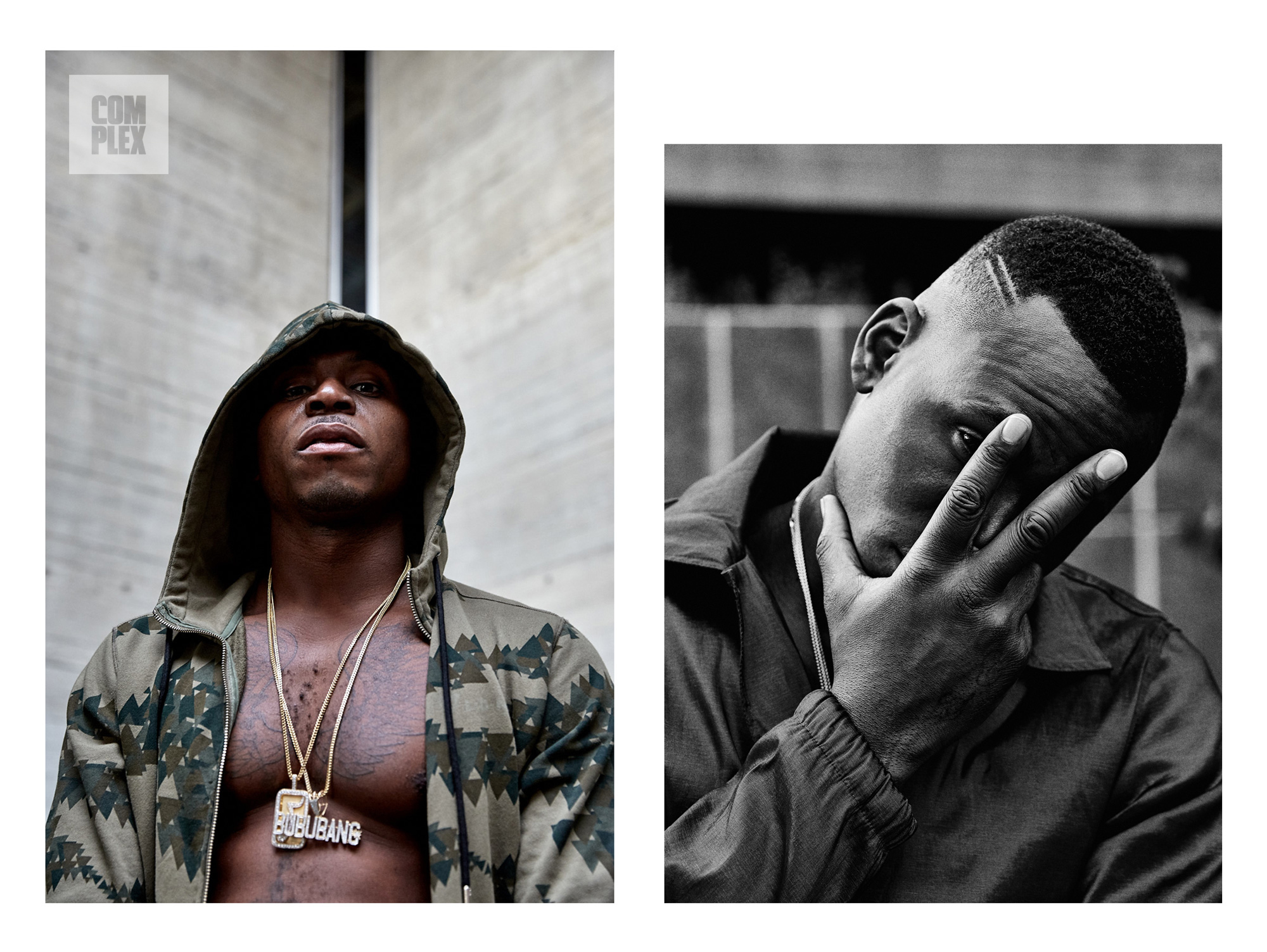

Fekky is like marmite: you’ll either love his trap-spirational style, or you will absolutelyloathe it. His nasal flow and ad-libs are a required taste, too. But for the past five years, the rapper from Lewisham, South East London, has worked his way through the music industry to become one of the country’s leading—and shiniest—rap artists. Unlike most, Big Fek’s story isn’t a rags to riches tale: he had it before the music, and had been known in music circles as the trapper that raps—the one who would always find himself on the mic at local raves and house parties. But a real passion for rhyming was ready and waiting to be realised.

In 2012, Fekky began to focus more on the booth, which was when he dropped “Ring Ring Trap”, his breakout tune that became a hood anthem in a matter of weeks. He continued to release club-focused bangers independently up until he got signed to Island in 2015—which was also the year he teased El Clasico, his debut album. With the project, featuring Skepta, Chip, Ghetts, Giggs and more, finally out after two years of teasing fans—and in a time where Chicago drill-inspired rap is prevalent in the UK—Fekky is sure of his place in the scene and confident he’s released some of his best work yet.

But, as he explains to Complex...

“It still feels like I’ve got so much more to do.”

It feels like we’ve been waiting forever for El Clasico to drop—two years, at least. What was the initial hold up with the project’s release?

Just life! Touring; I do shows all over. But I had made the album before. I’ve made it twice before, but I feel like I made them in a rush. So I took time out and actually made a proper album that I am happy with. All the projects I made before, the great ones, you can tell I put proper work into them.

Tell me more about the title, El Clasico, and the kind of topics you’re tackling on there. What kind of things are you talking about?

The title comes from the Real Madrid v Barcelona game. I was on tour around Europe and I ended up stopping off to do some recording in Barcelona. It just came to me when I was in a taxi and the driver was telling me about El Clasico, and about the clash. It basically means a classic. On the album you’ll get your normal shut-the-place-down Fekky, but there’s also a lot of substance. I feel like when I came into the game, a lot of people knew who I was from the streets or whatever. As I was getting older, the people that were in uni and college then, they’re like 25-odd now; they’ve got real lives, they’ve got kids, and they’re less excited about what’s going on. And then there’s the generation coming through that might not know that’s Fekky from those days there. I learnt so much about me, as a person, on this album. When you go through it, you’re gonna be like, “Rah! Fekky went through that?” You’ll learn a lot about me.

Without comparing you to anyone else, what makes this—your debut album—stand up against the more recent rap greats, like One Foot Out (Nines) or Common Sense (J Hus)? The British rap scene is super healthy right now.

El Clasico shows my journey, and you can see the growth. Sonically, just the little sounds on there, you know that this guy knows what he’s doing. We literally broke every track down like a car and built it back up, modified it. I just feel like this album doesn’t sound like those albums; that’s what makes it stand out in its own lane. You wouldn’t be able to get this from any other artist. That’s not even being big-headed—I’m just being real. If you want a certain thing, if you want this album, you have to come Fekky’s way. JP, you know me; I’m just trying to humble it down. Growing up, I’ve always known people might think that I’m arrogant, but it’s confidence. I just play the field that I’m in. I just know you won’t get this album from anyone else [laughs]. The variation of flows... Every song, sonically, they have their own sauce.

I first heard your name pop up in 2012 when you dropped “Ring Ring Trap”. It’s a banger that still rings off in clubs today, but I’ll be honest: back then, all I thought was, ‘So here’s another roadman trying to rap for hood fame.’ In the years since, you’ve proven me wrong and shown that you are actually invested in the music. Did you get a similar response from people when you first came out, or am I being too critical?

Nah, I agree with you. At the end of the day, even I didn’t know what was going to happen. What you said was entirely my mentality. I didn’t really give a shit! I was just a guy putting out music. I was getting in trouble, caught a few cases and that... At the time, I didn’t want to be on the streets getting into trouble. So I had time, and a bit of money in my pocket, got some equipment together and made some music. The minute I saw that I couldn’t walk down the street and I’m putting merchandise out and selling it out, all these things just opened up a lane in my mind where it’s like, “Yo fam! You’ve got something going on.” The minute I did a tape or two, I started getting booked and making money—legitimate money. That’s when I made the decision to take music seriously. It was hard, though, because the streets never want to let you go. When you’re from a certain area, and you’re a high calibre guy from that area, people are always gonna lean on you and want to be part of it. Not everyone’s going to take it as seriously as you. So I had to make that decision for myself, like: “Fek—what do you want to do? If you’re going to do this, do it all the way.” And it’s carried me all the way from there, to now.

Have you had to move differently since becoming more known? You could literally go to any hood in the UK, and they will know your face.

That’s the part that I find hard because I’ve never wanted to move different. Even the other day, I was with someone. I’d done a show in another country and when we finished, they were saying to me: “You need to move differently. You need to have more security around and stop people being able to touch you.” I’m that guy who never wants a fuss to be made about him; make a fuss about my music, but I’ve never wanted to feel like I need protecting. But I get what they were saying. It’s hard losing yourself in the game. Now, I have to be prepared that my shopping trip might take a few extra hours because I’m stopping every minute for pictures and talking to fans.

It comes with the territory, I guess.

Yeah, and you’ve got to adapt to it and make it work in your favour.

Where does Fekky see himself in today’s rap scene? Are you still on the rise, or do you consider yourself a bit of a veteran in the game?

That’s a hard one. I hate when people call me a veteran because all the veterans that are out there have been around for 10-15 years. They’re like five albums deep and they’ve done a lot. Maybe because I’ve done songs and I mix with a lot of legends, people put me in that bracket. So I wouldn’t want to be called a veteran yet because I haven’t accomplished half the stuff I want to do. The music thing, I’ve done very well for myself and I’ve built my name and my brand up so sick. But it still feels like I’ve got so much more to do.

What would you say is your biggest hit to date?

“Still Sittin’ Here” is probably my biggest. Or “Bu Bu Bang”, which is like [Lethal Bizzle’s] “Pow!” in the clubs. That’s where you look back, like: that’s the song that makes you a legend. That song never dies, from the day I brought it out. But “Still Sittin’ Here” is a bigger song. I can step on stage anywhere; Chase & Status brought me out in front of 50,000 people and literally everyone knew the song.

“Still Sittin’ Here” was a major look for both you and Dizzee—he definitely needed that fresh underground exposure. How did the two of you initially connect?

It was all organic. I made the song, he followed me on Twitter maybe a week or so after, and I just DM’d him. At first, all I wanted was for him to be in the video. So I sent it to him and he literally told me he’s not gonna do it, and then he did a verse! The verse came about a month later. I couldn’t believe we done it. Dizzee’s one of those people: he’s very stuck in his ways. He never does anything he doesn’t want to do, and so that made me realise he did the verse because he wanted to do it, because he loved the tune.

Unlike most UK rappers, you’ve worked closely with members of the grime scene and I think you’ve definitely got a grime energy when it comes to the live stage. Have you always been a fan of the genre?

Going to house parties, emcees would be on the mic, so I’ve always grown up with that in me. You’ve heard “Way Too Much”, with Skepta; you’ve heard “Avirex”, with Chip and Neutrino... I feel like I don’t get enough energy as I want to out of rap, and grime is much more natural for that. The next thing up from grime, is jungle. But I’m not gonna be doing jungle any time soon [laughs].

[Laughs] Fekky on jungle would be wild.

Here’s the thing I like about grime fans: they’re very clued-up. They’re not like pop fans or fans that are just there for whatever they heard on the radio, then the next person comes along and they follow that person. Grime fans are very loyal and they know what they’re looking for. And I feel like they can see that I’ve naturally got grime in me. That’s why they’re always into what I’m doing. I’m gonna do a bit more grime, in fact. After “Don’t Call Me Again” with Ghetts, and all the love I got for it and everything about it... I might even collaborate with a sick grime producer, like Rude Kid or someone. Even Rapid—get a little EP done. Or I might do it with a grime artist.

What was being played in your household as child, and is there a specific song or album that inspired you to become a rapper?

My dad played everything in the household. He’d play everything from Fela Kuti to country music, gospel music, Bob Marley... He’d play every single thing you could think of! On a Sunday, my house was like a constant rave. My dad used to have these Jamo speakers; then he had these stacked decks with like the amp, the equalizer. Proper sound man ting! [Laughs] He was really into sound. I could wake up in the morning and hear anything from Bob Marley’s “One Love” to “Zombie” by Fela Kuti. And then he’d throw on some R&B. In my house, I was very clued-up on music and the different types of music. And bass lines! That’s why my music’s so bassy: as a kid, I’d be in my room and I’d always hear the bass first through the speakers. As for other rappers’ music I was into, I’d say 50 Cent mainly. When he came out with “Wanksta” and the video with all the hummers rolling down the street, everyone in bulletproof vests, I was like: “Yo! Who’s this?” I believed him as well.

And I think that’s why people connect with you: they know that what you’re talking about is real-life stuff.

Exactly. If I said I was on top of a table with twenty bottles, everyone knows that’s Fekky. Or if I said I threw someone across the table—everyone knows it’s true. And that’s it with 50. This guy can’t know so much stuff and not know the streets.

I respect the chance Benny Scarrs and Darcus Beese took on signing you to Island—you got signed when really only Giggs had been doing mainstream looks for UK rap. Talk me through that process of them reaching out to you, and you signing on the dotted line.

I had about four labels after me when my Fire In The Booth went viral. A lot of people were calling me for meetings and stuff. I didn’t want to get signed for the money, because that’s something I already had. It was more about finding a team that could back my vision. I went to all of these big meetings but when I walked into Island, I saw people that were just like me. Benny hollered at me, and he’s another black guy trying to get it done like me. Then when I walked in there, I saw Darcus and thought to myself: “This is the kind of label where I can be me and not have to change up who I am.” So they were all bidding and whatever, but I already knew what label I was gonna go for. It’s been a hard process, though. A lot of people wonder why I haven’t put out more music, more albums and all the rest of that stuff, but it’s hard when there are so many chefs in the kitchen. As an artist, I have to keep an eye on everything. It’s not easy and I can see why a lot of artists got dropped and their careers went the way they went.

Obviously, we’re not trying to put a jinx on it—but if the album doesn’t do well, what would happen?

Whatever happens with my album, it’s done well. I can’t put everyone else’s pressures on me. My album’s sick, mate. Whether you listen to it now or at the end of the year, or next year, the fact still remains: it’s a sick album. The only thing is whenever I put anything out, I get very anxious. I don’t know what it is, but it’s like you’re about to put something big on the streets. But I’m not worried about sales or nothing like that. My album is going to live, no matter what. It’s El Clasico! And I know what I do music for; I know who I am. No one can box me off like that. It’s my first album, bruv! A lot of man who are selling out albums now, go back in history—they weren’t doing nothing with their first album. It’s a process that you build up.

“I’ve naturally got grime in me.”

Random one: what are your thoughts on the UK drill movement? Personally speaking, I like it—and I get it—but a lot of the beats and flows are beginning to sound samey.

It’s good, but I feel like what you said: a lot of it is the same. Everyone in that movement needs to know how they’re going to excel. If you remember, back in the day, everyone sounded the same. Everyone was MCing over grime beats. A lot of the MCs sounded the same, and a lot of the beats were the same. They were all ending up on the same beats at the same house parties. But certain artists took it upon themselves to separate themselves and make themselves stars, like Wiley and guys like that. It’s like the Afrobeats movement—a lot of the artists use Auto-Tune. But then you’ve got J Hus and Kojo Funds who’ve taken it in different ways and made it their own thing. That’s what some of the drill rappers need to do as well. I don’t think everyone should sit there and do drill every day. But it is interesting. Some sick bars are coming from UK drill right now, but because a lot of it sounds the same, you might lose some of it. 67, K Trap, all them sort of people, they’re coming with that good content.

What are the next the 2-5 years looking like for you and the road rap scene as a whole?

I just feel like in the next five years, it’s in our hands as artists. It’s time to boss up and take control. It’s the artists who need to take control so we can have our Diddys, Birdmans, Dr. Dres, all of our bosses making sure that our stuff is around until the end of time. It’s in our hands, though. It’s down to us to manoeuver and stick together and really make a scene. We saw it before with Tinchy Stryder and Chipmunk—all of those guys. They were doing crazy stuff: they were on the telly and then, all of a sudden, it wasn’t cool anymore. Nothing’s a certain thing unless you look after it.

What about acting? You did your thing in The Intent. Could you see yourself doing more acting down the line?

Yeah... You know what it is? I just want to get past this album and achieve what I need to over the next few years. Everything that’s happened, I’ve seen it. I’ve said it, and it’s happened for me. But I get messages all the time about how much people love The Intent. There’s gonna be a second part to that film and I’m gonna be in it—which will be a lot of fun. But for now, I’m just focusing on getting this music out and I’ll think about everything else after.