It has been 15 years since Aaliyah died in a plane crash, ending a life and career that were only beginning to realize their full potential. The three albums she released while alive influenced some of today’s most significant artists—Drake, Beyoncé, the Weeknd, and many more. But you won’t find most of her music online. In fact, Aaliyah’s most popular, most important works—the albums One in a Million and Aaliyah, and late-career singles like “Are You That Somebody?”—aren’t available for streaming or sale on Spotify, iTunes, Amazon, or any other online music service.

Digital voids like these can result from legal battles over uncleared samples (as with De La Soul), or from musicians holding out for better royalty terms (the Beatles, until recently). Other times they’re the result of ideological stands against the devaluation of artistic output (Joanna Newsom), or cranky nitpicking about audio quality (Neil Young). But Aaliyah’s internet absence is different—there’s no logic to it. It’s not an artistic statement or a play for more money, and there’s no dedicated Aaliyah-only streaming service in the works.

Instead, there’s a single, stubborn man, sitting on a catalog that includes almost all of her most famous work, as well as albums from Timbaland and Toni Braxton, and a trove of unreleased original material that’s never before been heard. The situation puts her entire musical legacy at risk of fading from memory. Year by year, streaming accounts for a greater portion of an artist’s visibility and reverence among the next generation of listeners. And he refuses to budge.

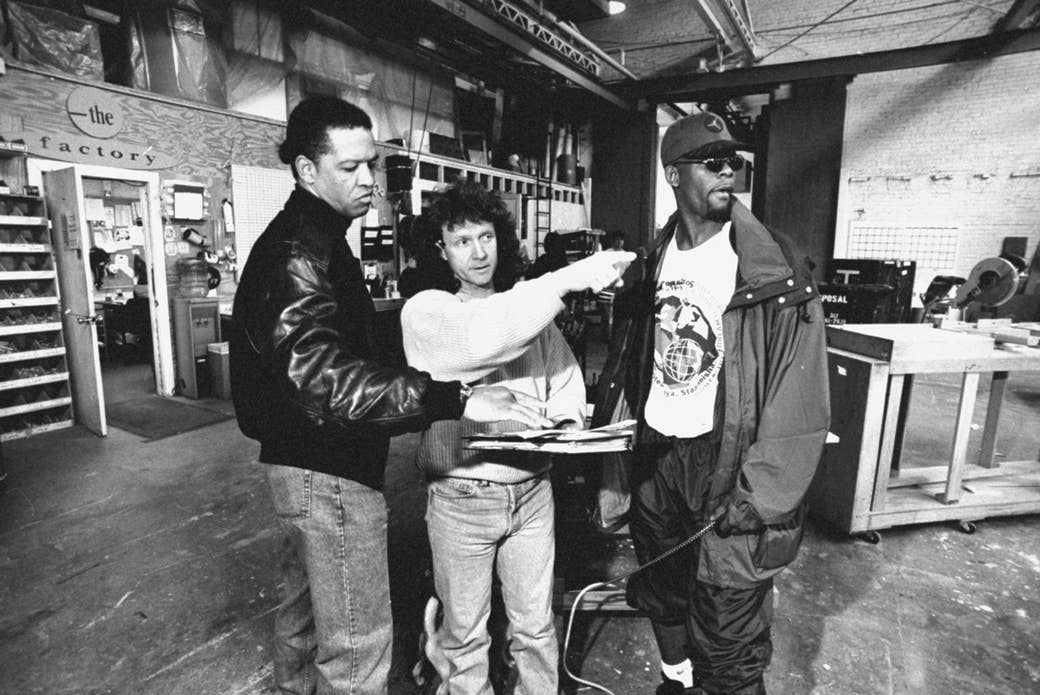

To understand Aaliyah, and the fate of her iconic catalog, you have to understand her uncle, Barry Hankerson, who groomed the singer for stardom from a young age as her manager and the co-founder of her label home, Blackground Records. The 70-year-old Harlem native was an extraordinary figure in the music business, who helped launch not just Aaliyah’s career, but also those of R. Kelly, Ginuwine, Timbaland, and Missy Elliott. But his achievements remain shrouded in mystery. “I’m consistently amazed by the things Barry Hankerson has accomplished,” says veteran music journalist Jim DeRogatis, one of the few members of the press ever to talk regularly with Hankerson, mostly during his long tenure at the Chicago Sun-Times. “He is this Zelig-like figure. Almost nothing is known about this man.” Despite multiple requests for comment, Hankerson declined to participate in this story.

Hankerson was not, by training, a music man. In the late 1960s, he attended the historically black Central State University in Ohio, majoring in sociology and developing a reputation as a campus radical. He also played starting safety on the school’s football team, and after graduation, had auditioned for a roster spot with the New York Jets. But he never made it past the development league, and hung up the cleats after a year, seeking a career in politics.

By the early 1970s he was employed as a community organizer in the office of Coleman Young, the mayor of Detroit. It was there that he first met the singer Gladys Knight, who was scheduled to perform while working at a local fundraising benefit. Love at first sight it was not. The taciturn, serious Hankerson viewed Knight as a “pampered singer,” according to a January 1975 Jet magazine cover story. Knight, in turn, described Hankerson as “very evil.”

But the two remained in contact, and within a few years they were married. It was an odd union. Both Hankerson and Knight already had children from previous marriages. Knight’s, whose signature hit, “Midnight Train to Georgia,” had just been released, was world famous at the age of 30; Hankerson, 27, was a complete unknown.

Hankerson began to use Knight’s connections and capitalize on her celebrity. He appeared with her on that Jet cover, sporting a tasteful leisure suit, a trim goatee, and an Afro. He convinced Knight to leave her backing band the Pips, and negotiate better terms with her label. He produced her movie debut, the aptly named Pipe Dreams, a box office flop about Alaskan oil workers. And, in his first foray into the music business, he started a management company to handle her affairs.

When they divorced in 1979, Hankerson abandoned Detroit politics for Los Angeles glamour. He spent most of the '80s pitching unproduced screenplays and managing a gospel group, the Winans. It was only after a decade in the trenches that he found his next breakout star: Robert Sylvester Kelly, a Chicago train station busker.

“I’m consistently amazed by the things Barry Hankerson has accomplished. He is this Zelig-like figure. Almost nothing is known about this man.” —Jim DeRogatis

Hankerson managed R. Kelly for the next 10 years and executive produced his first four albums. From the start, though, there was a problem: Kelly was a gifted songwriter and producer, but he was also rumored to be a sexual predator.

Tiffany Hawkins, one of his earliest alleged victims, met Kelly in 1991 at the age of 15. Enticed by promises of stardom, Hawkins claimed in a civil suit that she had sex with Kelly, and that he had her participate in group sex with other underage girls. When Hawkins turned 18, she says, Kelly dumped her. She attempted suicide. Numerous other young women would make similar allegations in the years to come; Kelly avoided conviction, often opting for out-of-court settlements.

How much did Hankerson know? It’s impossible to say. Still, if he had indeed heard or suspected anything—at least in 1991—it wasn’t enough to dissuade him from introducing Kelly to his 12-year-old niece, Aaliyah Haughton.

Aaliyah was the daughter of Hankerson’s sister Diane. Her talent was evident from a young age. Born in Brooklyn and raised in Detroit, she competed on Star Search in 1989 and, at Hankerson’s urging, performed onstage with Knight. (Hankerson and Knight had by this time reconciled.) With her parents’ approval, Aaliyah agreed to let Hankerson manage her, and he signed her to a recording contract with Blackground Records, a boutique label distributed by Jive Records that he founded with his son, Jomo, in 1993. (Jomo declined to comment for this story.)

Hankerson served as executive producer on all of her albums; he managed her publishing and royalty deals; he surrounded her with some of the most talented musicians of the era. For her debut, he paired her with Kelly, who produced and wrote most of the songs on Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number, released in 1994. The title track, written by Kelly, was a hit, but in retrospect, it was also a not-so-coded reference to their clandestine sexual relationship. Aaliyah was 14 when the song was released; Kelly was 27. On August 31, 1994, they were secretly married, with Aaliyah claiming to be 18 on the marriage certificate.

After Vibe published a story about Kelly in its December 1994/January 1995 issue and included a copy of the fraudulent certificate, the marriage went public; it was annulled shortly thereafter. Hankerson, reportedly furious, permanently separated Aaliyah from Kelly, but he didn’t cut his own business ties with him until years later, in 2000. Kelly, at the time the most popular R&B singer in the world, was too valuable.

In 1996, after striking a distribution deal with Atlantic Records, Hankerson moved Blackground—and Aaliyah—from Jive to Atlantic, gaining full control of her masters in the process. To replace Kelly, he recruited an emerging songwriting/production duo from Virginia Beach, Missy Elliott and Timbaland, to work on the next album. Released in 1996, One in a Million went double platinum on the backs of singles like the title track and “If Your Girl Only Knew,” which both became radio hits thanks to Timbaland’s innovative production style, Elliott’s memorable hooks, and Aaliyah’s effortlessly icy vocals. Hankerson quickly signed Timbaland to a solo deal, along with his collaborator Magoo, but Elliott defected to launch her own recording career, leaving Blackground short a songwriter once again.

Hankerson signed a Timbaland collaborator from Louisville, Kentucky, named Static Major, and over the next four years the pair turned out some of the best songs of the era, including Ginuwine’s “Pony,” in 1996; Aaliyah’s greatest single, “Are You That Somebody?,” in 1998; and “Try Again,” her first and only No. 1 hit on the Billboard Hot 100. By the turn of the millennium, she was an international star.

This was peak Aaliyah. Her music was tight, upbeat and complex, layering double and triple harmonic lines. Her voice, in isolation, was not among the all-time greats, but her whispery presence on a track was captivating. Her angular, syncopated dance moves spawned dozens of lesser imitators, and her fashion choices—the oversized jeans, the exposed midriff, the waist chain attached to the belly ring—became definitive late '90s style.

Her self-titled third album launched in July 2001. Though it was pitched against the difficult headwind of widespread online file sharing, Aaliyah managed to go platinum twice, thanks to singles like “Rock the Boat” and “More Than a Woman.”

Six weeks later, at the age of 22, Aaliyah was dead. She’d been shooting the music video for "Rock the Boat" in the Bahamas when her plane crashed immediately after takeoff. Carrying eight people and luggage, the plane was overloaded. Its pilot, Luis Morales, had obtained his license by falsifying his flight logs. An autopsy revealed traces of cocaine in his system.

Hankerson was devastated, retreating into a long period of grief. He made no public statements about her death. According to those who worked with him, he never really recovered.

In February 2002, seven months after Aaliyah’s death, Chicago Sun-Times reporter Jim DeRogatis received an anonymous videotape in the mail, showing a man who looked exactly like R. Kelly urinating into the mouth of a underage girl. DeRogatis, who had already been investigating Kelly’s reputation as a statutory rapist, immediately turned the tape over to the police. In a published transcript with the victim’s mother, DeRogatis later speculated on the identity of his source, using initials instead of full names: “I’m sure that tape came by B.H.,” he said. “He’s tired of seeing young girls get hurt.”

Hankerson had split with Kelly, acrimoniously, sometime in 2000. When I talked to DeRogatis recently, nearly 14 years after the infamous tape first leaked to the public, he recalled Hankerson fondly. “I always found him to be a man with a conscience who felt wrong by his niece,” he told me.

For a brief period after Aaliyah’s death, it looked like Blackground might survive. The label still had Timbaland and Static Major. Hankerson had managed Braxton since 1997, and, in 2003, he inked her to his label as well. He signed Aaliyah’s possible replacement, a 12-year-old named JoJo aimed at the Radio Disney demographic. And he had the unreleased, unmixed vocals of Aaliyah’s outtakes—more than a dozen potential songs on two-inch reel-to-reel tapes. All they needed was a producer.

According to Hankerson’s eventual business partner, Rell Lafargue, COO of independent music publisher Reservoir Media, Hankerson never found one. He couldn’t find the sound he thought the music deserved. And the wound left by Aaliyah’s death remains raw: “Barry can’t be in the room when the new music is playing,” says Lafargue. Grief turned to despondency; despondency turned to inertia. Inexplicably, Blackground stopped releasing music, and artists stopped getting paid. As the music business moved from CDs to MP3s, and MP3s to streaming media, Blackground didn’t participate.

Soon the lawsuits started. In 2007, Braxton sued Blackground, claiming a breach of trust and misrepresentation and accusing Hankerson of “fraud, deception, and double-dealing.” In 2009, Timbaland sued as well, alleging that the label had refused to provide financing for his third album with Magoo and that Hankerson was interfering with his career as a producer. (Timbaland and his lawyers declined to comment for this story.) In 2013, JoJo filed her own suit, alleging that Blackground had refused to release her third album for more than six years, despite the fact she had delivered numerous audio masters to Hankerson.

That same year, Jeffery Walker, a former producer for Blackground, sued the label after being sent a tax bill from the IRS for more than $200,000 of reported income he says he never received. Walker’s lawyer claimed that Hankerson’s son Jomo had endorsed the checks himself, then cashed them in a Blackground account. The case is ongoing.

All the other lawsuits were settled out of court, with the parties signing confidentiality agreements. Speaking with the Fader earlier this year, JoJo, who’s now signed to Atlantic, described this period in her career: “I’m not entirely clear on what I’m not supposed to talk about, because I want them to leave me alone. It was such a strange and scary time. Threats and a lot of drama.” (JoJo declined to comment for this story.)

The pattern in these lawsuits was similar. Hankerson’s lawyers would contest every filing and push for changes of jurisdiction, generally seeking to delay things as long as possible. “They use every available means to crush you into a powder,” said Kelli Hooper, a lawyer who formerly represented Walker. “That’s what Blackground does.” Once the legal tactics were exhausted, the cases entered the discovery process, where Hankerson might be deposed under threat of perjury. At this point, Blackground would unexpectedly settle. “Concerns about testifying under oath may have led to settlement in this case,” said one lawyer employed by a Blackground plaintiff, “and perhaps others.”

“It’s not above Barry Hankerson to have someone call me impersonating a reporter." —Neil Sunkin, Attorney for Kyme Dang

Another lawsuit, filed in Los Angeles court in 2007 by Hankerson’s former girlfriend, Kyme Dang, contained the most explosive allegations. It was contested bitterly—in fact, when Complex called Neil Sunkin, Dang’s attorney, for comment, he requested multiple forms of identification. “It’s not above Barry Hankerson to have someone call me impersonating a reporter,” he said.

Dang is a Calabasas, California, hairdresser who began dating Hankerson shortly after Aaliyah’s death. The two were together for five years, and even lived together for a time, but after Dang ended their relationship in late 2006, Hankerson tried to destroy her life, she says. First, he began spreading rumors about Dang online, falsely alleging that she was HIV positive. Then, using the money he had earned from Blackground, he purchased the hair salon she worked at and fired her. Finally, she alleges, he tried to blow up her car. “It was set on fire, totalled, and all charred up,” she says.

Hankerson’s lawyers denied the allegations, and he was never charged in connection to the arson, but the rest of Dang’s story was corroborated when she sued Hankerson for wrongful termination. Evidence presented at trial showed the source of the HIV rumors was an IP address connected to Hankerson, and business records proved he did indeed purchase the Frank Grecko Salon where she worked, paying $400,000 for the privilege of firing his ex.

In this case, Hankerson refused to settle. That was a mistake. The evidence against him was overwhelming, and the jury sided with Dang, awarding her more than $5.8 million in damages. Following the decision, Hankerson told Dang’s lawyers that the judgment would bankrupt him personally, and that if they wanted to get paid, Blackground Records would have to act as a guarantor for the debt.

Dang’s lawyers agreed, but, they say, Hankerson failed to honor the deal. In early 2015, Dang sued again, alleging that she hadn’t received any of the money she was owed, and that Blackground was in default. By this time Blackground had ceased to function as a business, and its musical catalog, representing a revolutionary moment in the history of R&B, had disappeared from the internet. The only confirmed instance of songs from One in a Million and Aaliyah appearing on a digital music service occurred in 2013, when Craze Digital, a distribution company that never owned the rights to Aaliyah’s music, illegally posted them on iTunes. After a round of litigation, the tracks were removed. A request inquiring about Aaliyah’s past availability on Spotify went unanswered.

In 2012, Hankerson sold a stake in Blackground’s publishing rights to Reservoir. The centerpiece of the deal was Aaliyah’s tapes. “At the time we were talking about releasing it for the 10th anniversary of her death,” says Golnar Khosrowshahi, Reservoir’s CEO. “Now it’s the 15th.”

Khosrowshahi explains that her relationship with Blackground has been frustrating, but that she wasn’t disappointed with the deal. She has struck deals to license Aaliyah samples to a number of rappers, including a snippet of the unreleased material that appeared on ASAP Rocky’s “Fuckin' Problems.” And she was particularly enthusiastic about the Static Major catalog, especially the publishing rights to Ginuwine’s “Pony,” which acts like a tax on every strip club in America.

She also promises that a final Aaliyah release is forthcoming. Several artists have already been rumored to be attached to the project, including Timbaland, Kanye West, and Drake. In fact, a single, “Enough Said” (featuring and released unofficially on SoundCloud by Drake), was slated to appear on a posthumous album that Hankerson announced would be available at the end of 2012. Unfortunately, the song only ended up further delaying the project. The Haughton family swiftly released a statement denying any connection to the album after the release of “Enough Said.” Aaliyah’s closest collaborators, Timbaland and Elliott, denounced it in a statement provided to Billboard by Elliott’s manager: “Although Missy and Timbaland always strive to keep the memory of their close friend alive, we have not been contacted about the project nor are there any plans at this time to participate.... Both Missy and Timbaland are very sensitive to the loss still being felt by the family, so we wanted to clear up any misinformation being circulated.”

In 2014, Drake and his long-time producer, Noah “40” Shebib, backed off from the album. In an interview with Vibe, Shebib said that he “wasn’t comfortable” working on the project any longer after the negative press surrounding “Enough Said” created, according to him, a “stigma” around their involvement. (Earlier this month, another song from the project, “Talk Is Cheap,” was leaked to the web but failed to generate much interest, perhaps a confirmation of Shebib’s fears.)

Since then, some progress has been made. “They have some great vocals on it, and a lot of production,” says Lafargue, who arranged the deal with Blackground and has heard some of the tracks. “They’ve kept it true to Aaliyah’s style.”

LaFargue thought the final Aaliyah album would be finished before the end of this year, although he admits he has thought that every previous year.

Right now, the only Aaliyah album legally available online is Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number, the one that Hankerson doesn’t control the masters for, and the one where she sings lyrics penned by the suspected pedophile she was fraudulently married to. This does not honor her legacy.

As the years pass, there’s a bigger risk—that Aaliyah will be forgotten. Nostalgia is cyclical, and Aaliyah has already peaked as a fashion icon on Tumblr. Right now, the music industry is the midst of a shift to an all-streaming landscape. When the transition is complete, if Aaliyah's catalog isn't on the right platforms, her music could functionally cease to exist. Within a few years, she could transition from resurrected angel to period-piece obscurity. One day, if you want to understand what made her so important, you’ll have to dig out your Discman and pray you can still find a used CD copy of One in a Million or Aaliyah. And if that happens, Uncle Barry will be the one to blame.

Stephen Witt is the author of How Music Got Free. His writing has appeared in the New Yorker, and he lives in Brooklyn.