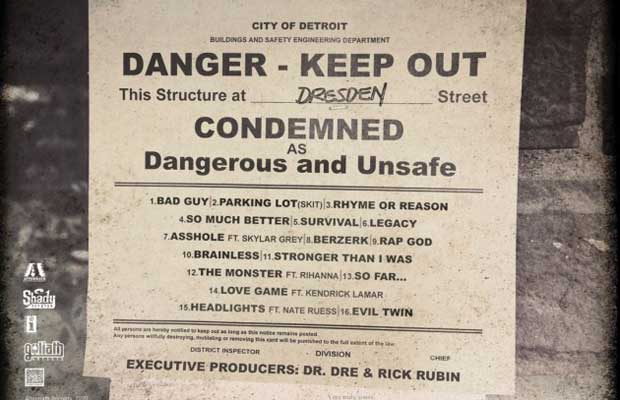

Last week, the tracklist to Eminem's The Marshall Mathers LP 2 leaked, and it prompted plenty of speculation on the project: It would be great because it includes Kendrick Lamar. It would be horrible because it features Skylar Grey. And who the hell is Nate Ruess?*

Actually, the prophesying could get even more ridiculous (OK, maybe that one was a joke), as folks online began to treat a list of words and a few scattered features like a Ouija board from which they could possibly divine the future of Eminem's career. Twitter Ms. Cleos across the world united to weigh in on the record's odds of being memorable, forgettable, or somewhere in between. (Conclusion: "This could be really dope or really bad...") A few common English words and some big-name stars became the album's DNA, a script that could tell us the record's entire story.

No doubt there are a few moments on the tracklist worth idle speculation. For those interested in the horserace of current lyricists, determining whether Kendrick Lamar can stand on the same ground as one of his clear inspirations obviously has the potential to be a big deal. Of course, if you look to closely, all that anticipation explodes into meaninglessness: It could be a major torch-passing verse. It could be an embarrassment for one of them, when the other raps circles around him. It could be a deflating, underwhelming song that finds both artists utilizing auotune while singing dour hymns about the dangers of cartoon and cereal addiction. Maybe Em just did the beat. Maybe it sounds like Yeezus.

Certainly the most high-profile example of the mis-lead single was when Lady Gaga was rumored to be making an appearance on Kendrick Lamar's good Kid, m.A.A.d. City. Her version didn't end up making the final cut (which was, in the end, a smart decision—the Gaga-less album version is a stronger track, point blank). But her name alone definitely set some unusual expectations for an album that would end up being hailed as an instant classic. More recently, Danny Brown's Old featured a guest spot from Charli XCX, a brash young electro pop singer whose style wasn't nearly at odds enough with Danny's brash indie-friendly abrasiveness. Surely they'd record an electro-spasming Williamsburg floor-filler. But instead, the duo ended up making a low-key track of tasteful psychedelia.

But while it might be fun to play games of what-if for a moment, acting as if it's a predictor of how a record will actually sound is a fool's errand. No doubt an all-No ID-produced Common record with a slim guest list (Nas, Maya Angelou, and John Legend?) had Common purists salivating. But however promising that record may have looked, it's clearly missing the x-factor that made Com's earliest collaborations with No ID so incredible. (Twitter ca. 1994: "Dog, who the fuck is Y-Not Never the Less? Where's Nas?")

What this means, of course, is that tracklists now create a perception of what the product will be—and, perhaps, proceeding to undercut it.

The endless guessing game that greets tracklists has more to do with the pedigree of the names involved than it does anything about the organic process involved in creating a record. Look at the way producers make their names: a couple of hits and the next Young Chop or Childish Major becomes a brand. His prices go up, his tracks begin to fill in the cracks on other people's mixtapes. You download an Ace Hood tape because, hey, maybe Young Chop has some joints on there. But ironically, the song that makes his career was probably sold for a dollar and a dream. Keef got "I Don't Like" for free (probably). Rocko likely paid less for "U.O.E.N.O." than any major artist has paid Childish Major since that moment. But the real-world value of Childish Major's work on that song is much greater than any of his subsequent material.

What this means, of course, is that tracklists now create a perception of what the product will be—and, perhaps, proceeding to undercut it. Sometimes it's easy to overplay your hand. Consider underground rap duo N.A.S.A., whose The Spirit of Apollo attempted to throw your iTunes in a blender. Not to say that the album is bad, but the notion of Tom Waits and Kool Keith, John Frusciante and the RZA, or Sizzla and Amanda Blank knocking out tracks together is much more entertaining in the abstract than could ever be delivered in reality.

This kind of gaming the system might not be a bad move on their part. Like in politics, the day-to-day horse race and "optics" tend not to matter as much as the fundamentals, and for some artists, making waves with your tracklist might be better than nothing. Big Boi's Vicious Lies and Dangerous Rumors was a divisive record, relative to his prior album. It definitely seemed like he was taking a lunge at some blog relevance, and for a distinguished legend this wasn't the most tasteful branding decision. But this deep into his career, it was almost a way of trying to maneavuer himself out of the corner he'd been painted into. Although he's one of hip-hop's most respected names, he was no longer a major presence on radio, and despite its faults, the album was a unique effort.

The notion of tracklists even being news in the first place—like, a thing that fans would anticipate or even be aware of—is a new thing for the music business. The way tracklists were used when the first Marshall Mathers LP dropped was radically different. The biggest challenge in reading the album's song list back then was trying to figure out what it said beneath the bend in the plastic of the security case used to protect the CD from making its way out the doors of Warehouse Music under a shirt. You'd go all the way through the record, then skip back to your favorite tracks while trying to figure out what the hell a Dido was.

The funny thing is, if you saw Dido on a tracklist before hearing the song in 2000, it probably wouldn't have seemed that exciting. That "Stan" became a cornerstone of Em's career, one of his most celebrated narratives? That only seemed like a possibility when you heard the song. The tracklist was simply a guide. All you could see was a digital readout of the track number while you skipped from song to song. And you were definitely listening to each track, because dropping $18.99 on a single CD was a commitment of four hours of scanning items and wiping down your conveyer belt with cleaning spray at the Price Chopper. Also, dinosaurs ruled the earth, and cars were propelled by our feet a la The Flintstones.

The point, though, is that music was primarily a consumer good, rather than the marketing tool intended to hook you into dropping $80 on a concert ticket later in the year. The tracklist was simply a guide to getting through the record. Just getting you to buy the damn CD was enough to fund a rap label's cocaine fantasies. Now, each making-of video, advertisement, and cover art release becomes its own rollout, in an attempt to generate the kind of enthusiasm that used to exist in the pre-internet rap industry. And every time a tracklist is posted, it's measured for arbitrary suggestions of "Classic"-ness. Where's Nas? Why are there multiple producers? Why is a pop singer on this?

It's a part of the Classic Album fetish that has inundated hip-hop in recent years. But everytime an artist aims in this direction, it doesn't necessarily work out in the artist's best interest.

*Nate Ruess is the lead vocalist for the band Fun.