Looking at one of Juan Travieso’s paintings feels like looking at an image—whether a photo on your computer screen or a glimpse of a rare bird in a tree—right before it disappears. Working methodically in his New Jersey studio, he tapes off angles, paints, peels off the masking tape, then tapes again to create the myriad geometric fractures that comprise a single painting. If you need a singular word to describe the 31-year-old’s work, it’s impermanence. You’ve got to catch the color while you can.

The exotic animals and endangered species depicted in Travieso’s paintings are pixelated into grid-like shapes and forms, reminiscent of 3D models. They look like digital renderings, but are created using strokes of the paint brush.

His work deals with two primary elements: organics and geometrics. The right angle of human construction, an angle that doesn’t exist organically, is in opposition—but also in forced partnership—with nature. The animals in Travieso’s pieces appear to be mid-pixelation, like they’re about to be wiped away. It’s that transience that interests him.

“When you look at my paintings and see these endangered animals, you have almost this digitalization taking over it or erasing it,” he says. “That’s also this idea of human touch, the eradication of a species. That’s all our doing. I guess that’s the way to differentiate the three dimensionality, the 45-degree angle, from the organic thing and how they’re both two separate things.”

Travieso grew up in Miami, and the dazzling, natural color palette of the 305 (and by extension, Havana) is present in his work. His style blends elements of pop and realism—also a nod to Cuban art—but those terms aren’t of much interest to him.

“The minute you put a label on it, it’s like ‘post-post-post whatever,’ and that almost demystifies and puts baggage on something. It weakens the work," Travieso explains, as he tapes off angles and paints, only stopping to use a blow dryer on his canvas. At this point, painting is as natural as talking.

"You label something, and it becomes that one thing."

His pieces, with their geometric shapes and grids, have an architectural quality to them. It’s almost surprising to learn he doesn’t have a past life as an architect or 3D graphic artist. It’s simply a style choice made early on that has grown into his defining aesthetic.

“I was always drawn to how both things came together, the organics and the geometry, just from a painter’s standpoint,” he explains. “It slowly started becoming this disruption, the human touch. That came out of people going to shows and saying, ‘Oh, my god, I totally see this idea of how [it looks like] you’re digitalizing, or it looks like it’s becoming data.'”

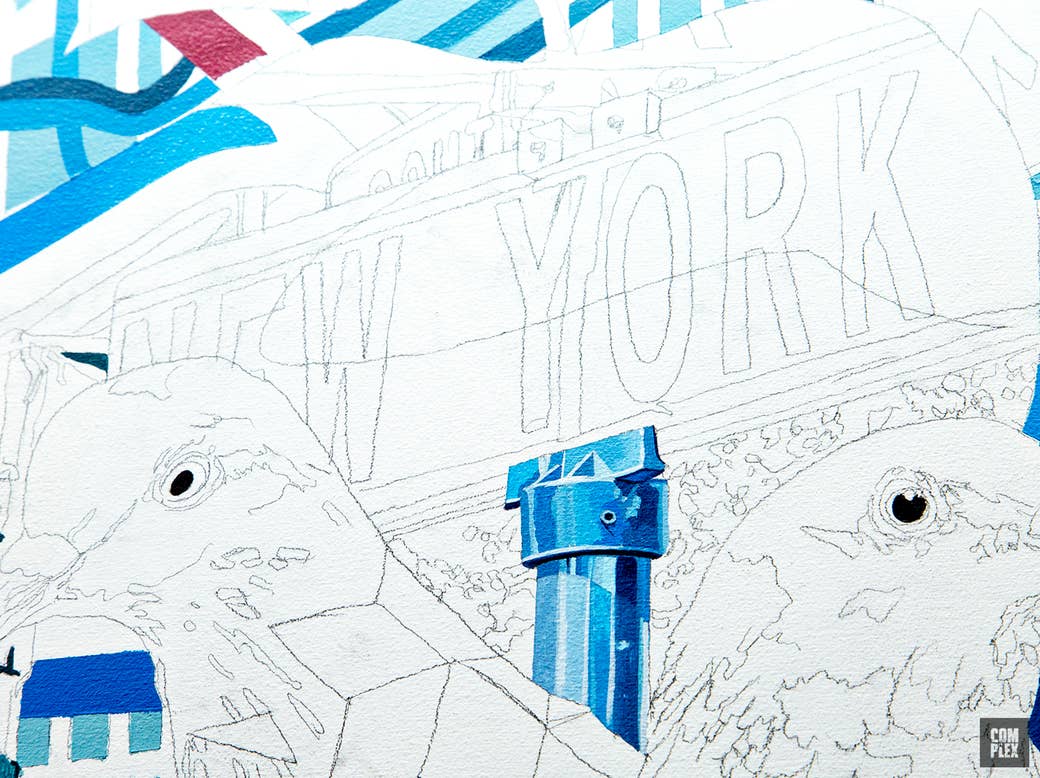

Travieso’s latest work is inspired by Adidas’ Deerupt shoe, whose mesh upper is overlayed by a grid-like webbing. The resulting two pieces depict New York City—one of the world’s most detailed urban grids—and represent the first time the muralist has explored the language of street signs on any type of canvas. A sign for New York’s “museum trail” is positioned above two pigeons, which are half-blanketed by rhombuses. A city grid comprises and connects the backdrop.

Grid lines, a defining theme in the artist’s work, this time serve as the backbone for an intricate collage of NYC life with instantly recognizable markers like subway signs and “I Love NY” stickers. In his other painting, the entrance to the 34th street subway station is depicted in the foreground, while a great dane stands at attention, eyes alert, if not appearing a little nervous.

Animals and their relationship with the environment around them are another recurring theme in Travieso’s art, and offer a sort of reimagination of city life with NYC’s wildlife, instead of its human citizens, as the main characters.

“Before, in the ’80s or ’90s, you had to be discovered. Now, galleries don’t solicit. They don’t even want you there. They want to find you online and discover you on their own terms.”

Travieso captures the energy of the city: always invigorating, frenetic, quick glimpses of nature on city streets. It’s a different atmosphere, he says, than the sunshine and pastel-filled atmosphere of Miami.

“When it comes to the living part of New York City, it takes a toll on your energy, whereas Miami is definitely more chill,” the artist explains. “Not to say that New York doesn’t have its serenity, but in order to live in it and coexist in it—and afford it—you do have to hustle quite a bit.”

In elementary school, Travieso painted his first mural, which was covered by the Miami Herald. Likely few of his contemporaries can tout the same accomplishment, but Travieso, possessing an innate understanding of color, geometry, and how they fit together, was truly born to be an artist.

Growing up, however, he wanted to be either a boxer or an archaeologist—two separate career paths that don’t outwardly relate to his current occupation. And yet, characteristics of both professions can be seen in his paintings: the mentality of an archaeologist observing the effects of human activity on the environment that surrounds us, and the fight and work ethic of a boxer. From attending Miami’s New World School of the Arts, to graduating from his master’s program in Boston and working as a full-time artist ever since, Travieso hustles.

“I’ve never been the most talented, and I’ve never been the most naturally gifted, but I work so hard,” he says. “In this career, you have to be extremely self-motivated, especially with all of today’s platforms. Before, in the ’80s or ’90s, you had to be discovered. Now, galleries don’t solicit. They don’t even want you there. They want to find you online and discover you on their own terms.”

It’s that blend of digital and physical that connects his work. Travieso says that one of the first things people ask when they see his paintings is if they’re digital.

“No, it’s totally physical, so it’s like I’m mimicking this virtual world that doesn’t physically exist,” he says. “I’m bringing it to life in a total archaic manner, which is painting.”

But Travieso acknowledges that what he does wouldn’t be possible in the same way pre-Photoshop. His process starts with the graphics editor software, where 70 percent of the creation is completed. Then, he sketches the image by hand in pencil, and may (or may not, depending) tweak the colors and images as he paints over the outline. Travieso will also photograph his subject—whether an animal or human—for reference as he works.

"When I read an article about the last male rhino dying, for example, I get inspired to do a piece about it. I’m really drawn to when things are on their way out."

The artists’ studio bookshelf in his strikingly pristine studio is lined with nature books. He describes how he derives inspiration for his subjects from these books and also from news articles he reads.

“Nature is key for me,” Travieso says. “When I read an article about the last male rhino dying, for example, I get inspired to do a piece about it. I’m really drawn to when things are on their way out. My work primarily deals with social and environmental issues. Those are my two main threads.”

In urban life, it’s clear that we’re the ones disrupting nature, and yet in a city like New York, the relationship between us and nature is so tightly (and uniquely) bound. Whether it’s the rats that scurry on subway tracks or the giant swaths of flora and fauna in Central Park that exist right next to skyscrapers.

“We often try to create a divide of, there’s a tree and that’s nature, but that building isn’t nature—but it is,” Travieso says. “In areas that aren’t meant to be ‘disrupted,’ like a sidewalk where it’s pavement, you’ll see a tiny little leaf come up. It’s almost a coexistence that’s happening. This idea of having an interruption or something that’s not meant to belong there or exist there; how the city and nature sort of play off each other. It’s a cycle.”