A$AP Rocky is sitting across from me at a table inside L.A.’s Sound Factory Studios. He looks away from the table, away from a sparse dinner he occasionally picks at, away from me, and repeats, under his breath, the two words I’ve never heard him say, and didn’t think I ever would: “No comment.”

To be fair, it’s been a long day, and he’s barely on the other end of it. A studio all-nighter that ended at 8 a.m. A photo shoot. This interview. A corporate fashion meeting. But despite his schedule, the “no comment” is still a surprise, even though it’s in response to a question about his love life. And not even a great one. It’s one of several times during this conversation where Rocky rolls his eyes, leans his head back—his braids dangling over the back of a studio chair—and stares into the ceiling in response to a question. He’s just not feeling it tonight.

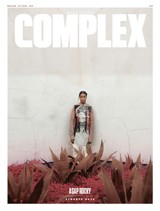

Rocky’s usually a talker. The 26-year-old Harlem native’s outspokenness has been well-documented in these pages and elsewhere more than a few times over the course of his young, white-hot career. His candor is part of his innate charisma: He’s never not had something to say. And typically, something that shows up on arrival as a classic Rocky quotable. So why’s he being tight-lipped now? Is it just the exhaustion from a packed schedule? Or a different kind of fatigue?

It’s hard not to consider the latter. In the two years since he released his chart-topping debut album Long Live A$AP, he’s also emerged as one of rap’s foremost fashion trendsetters, and landed in a relationship with model Chanel Iman. He modeled in a Ferragamo campaign, and took his first acting gig, in the indie darling Dope (a movie that—of course—ignited a fierce bidding war at Sundance for the distribution rights). Last October, Rocky’s first proper track in over a year, “Multiply,” was released to rave reviews. The song also made news because of Rocky’s jabs at fashion lines Been Trill and Hood By Air, two brands he’d provided crucial support to before. On New Year’s Eve, Rocky released the booming “Lord Pretty Flacko Jodye 2.” Fans freaked out. Clubs banged it. Writers praised it. A common headline emerged: 2015 was poised to be the year Rocky was back.

Then life got in the way. Barely three weeks into the new year, Rocky’s best friend, business partner, and, for lack of a better term, spiritual guru A$AP Yams passed away suddenly. Yams was there from the very beginning. When Rocky was up late on the phone before the fame, when fame was the plan, and the plan was to make it, to start a movement in New York that put a dent in youth culture through music, fashion, and art, it was Yams on the other end of the line. Always.

Understandably, Rocky’s hesitant when the topic of Yams comes up. “Everything [with Yams] was collaborative,” he says, in a low voice, dragging his words a little. “All decisions were 50-50. I would hear him out, and he would hear me out.”

Yams wasn’t just known for his instrumental role in the A$AP crew’s artistic development, but for an eclectic, finely tuned ear to the music scene of today and tomorrow, an incredible ability to discover new artists, and a razor-sharp wit—all of which informed Rocky’s music, his aesthetic, his ideas, his attitude. He was genuinely a tastemaker—a word thrown around all too often, but in this case, with good reason. Yams’ ear was special. And everyone knew it. Especially Rocky.

When Yams passed, a photo of Rocky clutching his hands in the hospital waiting room surfaced online. To this day, it’s probably the most poignant (albeit invasively captured) expression of mourning from Rocky on Yams. For 2015, there was a plan. And for the first time, not only have things not gone according to plan, but the guy he made the plan with isn’t there alongside him. It’s not hard to understand why Rocky might be on guard. Or why he might want to look away.

Earlier that night, after the shoot, we pile into his manager’s BMW 550 GT. Rocky takes the backseat, and asks if there’s anything he can roll weed on. It’s a 40-minute drive from Venice to Beverly Hills, where Rocky will meet with representatives from an iconic denim brand—we’re sworn to secrecy on the name—for an upcoming collection.

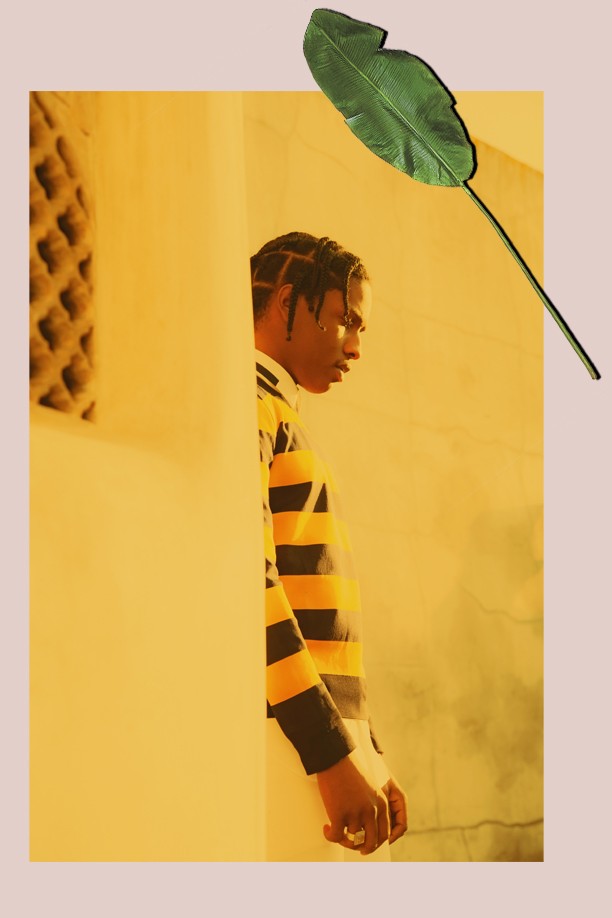

He uses his phone to start playing—at full, ear-splitting, bone-shaking volume—cuts from his new album, At.Long.Last.A$AP. It’s evident Rocky’s proud of the new work. He smiles as we’re listening to it, and taps his Raf Simons adidas from the backseat. After the album cuts, Rocky switches over to “Liar Liar” by the Castaways and “Gila” by Beach House (which he names as one of his favorite bands).

We head into the meeting. It looks like a department store exploded on the floor of the otherwise chic apartment; mood boards are everywhere. Executives stand around, and before long, they’re pitching Rocky on various pieces of clothing. As acid-washed jackets and denim bombers are being shown to him, Rocky chews on Sour Straws from a nearby snack spread, and begins replying to the pieces he’s shown in rapid-fire succession:

“Yes.” “No.” “No.” “Not feeling that.” “Change the paneling on that.” “Move the logo here.” “Keep it simple—it’s more about the lifestyle, not me.” “Too modern.” “No, we need to be more precise for the women.” “That’s good.” “No.”

Over the course of this series of exchanges, everyone in the room watches Rocky, hanging onto his every word to an obsessive, almost comical degree, as though they’re receiving the divine instructions, taking notes both mental and literal on everything he says. This goes on for a solid 90 minutes.

Back in the BMW, as we drive to his house off Melrose, Rocky comments on the Pacific Design Center building, his voice carrying a lighter lilt than it’s had all day: “You never realize how beautiful this building is until the night time.”

We pull up to Rocky’s house. There’s a black Range Rover in the driveway, even though Rocky doesn’t drive. Inside, Goyard bags are scattered throughout the living room. A TV is in the kitchen with an old-school Super Nintendo hooked up to it. Rocky takes a seat in the kitchen, and begins a FaceTime call with Chanel Iman (publicly, his ex-girlfriend). Iman—with whom he seems to be on friendly terms—has somehow locked Rocky out of his iPad. “No one told you to put a password on it,” Rocky smiles at Iman through the phone, and she jokingly fires back, “Shut up,” cracking the room up. After the iPad issue gets resolved, Rocky moves the call to his bedroom. He returns 30 minutes later in a Margiela sweater, a camel trench coat, black jeans, and crisp white and green Stan Smith adidas, ready to get back to the studio.

The drive to Sound Factory is short—about ten minutes. Plaques commemorating the Jackson 5, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Brian Wilson, and others line the walls. Vintage copies of Rolling Stone are sprawled across a table. Inside the studio, superproducer Danger Mouse is mid-conversation with MGMT’s Ben Goldwasser—someone Rocky’s always wanted to work with. “Heard the new shit,” Goldwasser shakes Rocky’s hand. “It’s dope.”

That night, Danger Mouse will float in and out of the studio as Rocky listens to beats and browses through WorldStar. At one point, he lands on a Vine compilation, and watches all 17 minutes of it, at times letting out loud cackles, which peak during one Vine titled “Thot Walk,” at which he completely loses his shit. After his food arrives, Rocky forks through it lazily, and starts in on the business of answering questions, however reluctantly.

You’ve been away from the spotlight a little bit. Was that a conscious decision?

Yeah. I needed time to master my craft. You don’t rush art, and I don’t think you quickly produce fine art. You take your time. That’s not an excuse, or me trying to justify [any delays], that’s truly what I believe. I took time off and learned how to act, learned how to make beats and do production.

How has the making of the music changed, then?

This is more free than I’ve ever been. I’ve never been this free making music, ever. I’m experimenting, listening, and looking for different sounds.

Looking back at Long Live A$AP, are there any regrets?

Yeah. I’ve got that cliché thing where I hate my biggest songs.

I remember Yams saying he didn’t like “Wild for the Night.” Would you ever make another song like that?

There’s no need to.

No? What other flaws did you see in the last album?

That album was rushed.

By whom?

Me.

Why?

I felt like I had to prove certain things that don’t matter. [That] I was capable of hit singles and platinum records. That’s not what I was ever after. That’s something that you just hope for.

In the three years since we last spoke, what has changed most about you?

I’ve matured. I’m 26. I view life way different. [Pauses.] A little more different. And I don’t give a fuck, still.

How do you view life differently?

I don’t take people for granted no more. Nobody’s promised tomorrow. I cherish everybody while they’re here right now.

Is that something that you didn’t do before?

Sometimes. I was oblivious. I did that by default. I was always away and getting caught up in my own life.

One of the new songs starts out: “Gentrification split the nation I was raised in.” It’s one of the more politically conscious things you’ve written. What do you see when you look at the state of America right now?

It’s fucked up. That’s all it is. Cops killing people, people killing cops. It’s all fucked up. I think it’ll all change soon. I think people with a badge—or not—are gonna stop abusing authority across the world, and learn to appreciate one another. For real. [Smiles.] All they need is weed, some love, some good sex, some good-ass music. I’m talking about a night with something exotic. I’m talking a night with like an African-Moroccan-half-Swedish-quarter-Italian-part-French-Parisian. Mhmm. But she got the African booty, though! She got caramel skin, but you can tell that like, she got a little bit of vanilla in her, though. You feel me? [Laughs.]

Sure. So it’s safe to say that women still inspire you?

I’m passionate about women. I look for ways to manifest that into my music. If they don’t get the message, then I’ll make something special for them. The message will get through one way or another. I love women. And I love the bitches.

What’s the difference?

There’s a difference.

What is it?

I’m not saying one’s worse than the other, but “women” got they shit together. “Bitches” is just out here, all burnt out with they heads cut off. Chickenheads. But somebody gotta love these hoes.

Are you single now?

No comment.

OK, let’s go back to an old relationship: How do you feel about the criticism of Iggy Azalea for not being an “authentic” rapper?

That [situation with Iggy] is unfortunate because nobody wants to be portrayed that way. I’m quite sure she doesn’t. I think she works hard like the rest of us. Silly or not, 300 million people like to watch it on YouTube, so who the fuck are we to say anything?

So you don’t think the criticism is fair?

It comes with the game. If she fake on something, somebody is going to call her bluff. That’s life. I’m not looking at it from a standpoint of “I used to be boning this chick’s back out.” I’m looking at it [as] “She’s just a person.” You can’t bluff. You gotta just be 100. That’s all I could really say. The question is: Was she not being 100 about something?

People feel like she’s manufactured.

She’ll be fine. It gets to a point where people start accepting so much mediocre shit—accepting the minimum and the typical—to the point where everything gets so oversaturated that people don’t have a choice but to go back to the original, hardcore, raw [art]. Everything raw. Every aspect of art. It changes and it makes shifts.

Speaking of changes, the Been Trill/Hood By Air diss in “Multiply” really made noise. What was behind that?

It’s really nothing.

A lot of people cared.

No one cares.

You know that’s not true.

I don’t even think it’s worth talking about. [Those brands] just didn’t acknowledge or respect my shit. I feel like I started all that and niggas didn’t even acknowledge my shit. Or respect my shit.

How did they not respect you?

The people behind the brands didn’t acknowledge me as a pioneer because I didn’t sit down and create the name Hood by Air with Shayne [Oliver]. I’m taking full credit for that brand, for anyone knowing anything. Yes. I’m taking credit for that. I liked it when I was way younger. It had a little run here and there, but nobody ever really kicked it off. I knew Shayne on a personal note. I was like: “Yo, let’s bring this shit back.” It took me years. Shayne’s stubborn. He’d give me a sweater one year, a T-shirt one year. It was like that. I have a lot of shit from back in the day, and I’d say after “Peso”—because we have Hood by Air in the “Peso” video—by the time it hit 2012, 2013, he was ready. Because I was out there in the field. I just made that shit look jiggy.

And what about Been Trill?

Come on, with the Been Trill. Don’t even get me started because you know. People want me to answer questions they know the answer to. There’s nothing to talk about.

Whether Rocky wants to or not, there’s plenty to talk about. After watching some more WorldStar, he politely asks us to leave the studio to get some work done with Danger Mouse. The difference between the Rocky of a few years ago and the Rocky of now is jarring, to say the least.

A little under two weeks later, I step off the elevator into the penthouse of his apartment building in Soho. Rocky—who’s consented to a second interview—is nowhere to be found in the dimly lit space. After a few minutes, he emerges from his bedroom, but only for a split second: “I’ll be right out, my stomach’s fucked up. Make yourself at home.” He disappears again.

Inside the living room, a painted portrait of Einstein hangs over a long wooden table, supporting a Mac desktop and an Alexander Wang ashtray full of blunt ashes. A purple light dangles from the long hallway that connects his bedroom to the living room. After a few minutes, he emerges wearing a gray robe and red Visvim slippers. He’s fresher, more alert than the night in the studio two weeks ago, but he’s still not exactly pouring his heart out.

Are you living a more private life these days? You weren’t even at New York Fashion Week heavy this year.

I’m not private like I think I’m Michael Jackson or some shit. I’m just trying to, I don’t know, distance this space between me and social media. Me and...just media in general.

Why?

It’s the cliché: The media’s good for twisting stuff up and making something out of nothing.

For you, that’s new. What changed?

Maybe I came to the conclusion I just didn’t wanna talk to some motherfuckers no more. Why do we go from liking blue today to red tomorrow? I don’t know. Motherfuckers change. When I wanna talk, I’mma do it. When I wanna be places, I’ll go. I prefer to be free. And I feel like when you live that life of paparazzi, media, social media, when shit hits the fan, they’re gonna be the same people that destroy you. So I don’t wanna give them the credibility of making me, because when it’s all said and done, the motherfuckers won’t be able to break me.

We talked about you being an artist before a rapper—

—There’s a difference. Let’s be clear on that.

Do you feel slighted when people call you a rapper?

No, because that’s gonna happen. That’s what I do. But I feel like nowadays, the term “rapper” doesn’t mean anything honorable.

How so?

When you walk through hotels in foreign countries, they assume you’re either an athlete or a rapper. It’s almost like: Rappers are becoming the new GED way out of things.

A few weeks ago, we talked about not rushing art. What’s going on with the album? Is it ready?

No matter what, it’s never enough time. You’re always gonna say, “Wait, give me two more seconds. Let me get a couple more minutes.” When you’re a perfectionist and trying to craft a really dope piece of art, shit...

Who were your muses for this album? And inspiration?

Michèle Lamy, my relationship status, my social status, Danger Mouse, just my life, my current situation with A$AP. And drugs.

What kind of drugs?

Psychedelics. Before it was all about the slowdown. Promethazine. Codeine flow. Now it’s like that, but on another level to the max.

Are you still taking them?

I use them to my advantage. It’s not something I wanna fuck with all the time. That’s the beauty of it. You can dip and dab with the psychedelics, but that ain’t something I wanna keep doing. Nah.

When we were in L.A., you were listening to a bunch of different types of music.

I’m going to be honest with you, man. When Yams died, psychedelic music healed me. Stuff like the The Mysterians, “96 Tears.” That’s all the stuff I love. I love classic rock. Take the Doors—those organs. It’s why I love Danger Mouse’s aesthetic.

I always loved the mantra of A$AP Bari’s clothing line, VLONE: “Live alone, die alone.” How does that play into your life?

If you look at the concept of birth and death it’s, like, I would rather be “VLONE” because you’re born alone and you die alone.

Is that something you feel like you live consistently?

For sure. Especially when you got loved ones popping in and out your life and shit.

Any plans for the day the album drops?

I might drop acid for A$AP Yams. Let me honor his name. [Pauses.]

I know you need your rock star moment. I know you need it! [Laughs.]

You got it.

We leave the table and Rocky brings me into his bedroom to listen to the album. The massive space is lit in an orange hue; a giant tapestry hangs over his bed, on which a Liberace-esque pile of gold chains is scattered. Rocky mumbles an apology about the room being messy: “I should’ve cleaned up,” he says under his breath, and then: “I had someone over last night.”

Clearly, something interesting was happening the night before. A webcam on his entertainment console is trained against the wall. I ask Rocky why a camera would be facing a wall; he says whoever was over last night did it. Shouldn’t he, the celebrity, be the one worried about having a camera on him, in his bedroom? He just mumbles back, sotto voce, “Well, she was famous, too.”

He cues up the music, lights a blunt, and motions for me to take a seat on one of several massive Goyard chests scattered around the bedroom. One track features Miguel singing over a sample from Rod Stewart’s “In a Broken Dream.” Another track wields verses from Juicy J, Bun B, and previously unreleased bars from one of his musical heroes, the late Pimp C. One song has Rocky singing in a falsetto (in the room, he warbles along to the track). Another, “Holy Ghost,” is ostensibly a searing indictment about rappers being slaves to their titles, but Rocky’s more interested in how it’s tied up in conflicts about spirituality. “I didn’t want this to get confused [as] bashing religion,” he explains, and then raps a few bars from the track after it’s done playing:

“Who’s more important than your lord and savior/Won’t let the pearly gates up, it’s probably due to all your poor behavior/My mental got a couple tips to save ya/You can count it as my only favor/thank me later.”

Every rapper talks about how their new album is different; how their sound these days is an evolution, a personal movement. Rocky’s tried to pass this stuff our way, too, but this time, it sticks: Nothing on the album sounds like the cuts the public’s already heard. It’s immediately clear that Rocky’s affection for psychedelia isn’t bullshit, or a put-on. The album’s a hazy, late-night, slow burn. It’s patently different, at least for Rocky, for what we know of him. Or, knew of him.

At one point back in L.A., in the studio, I tried to ask Rocky about Yams. The reply, like so many others that night, came swiftly: “You can ask the Yams stuff, but I don’t really talk on Yams.” He looked down. “I’ve spoken on it, I don’t wanna speak on him.” It was worth taking a final shot, one last question, one takeaway as to how Rocky tied the death of one of his best friends to his work, and whether or not it’s shifted something inside of him personally. That time, he answered:

“It doesn’t make me want to go harder, it lets me know I have to go harder. I don’t have any other choice. I have to.”