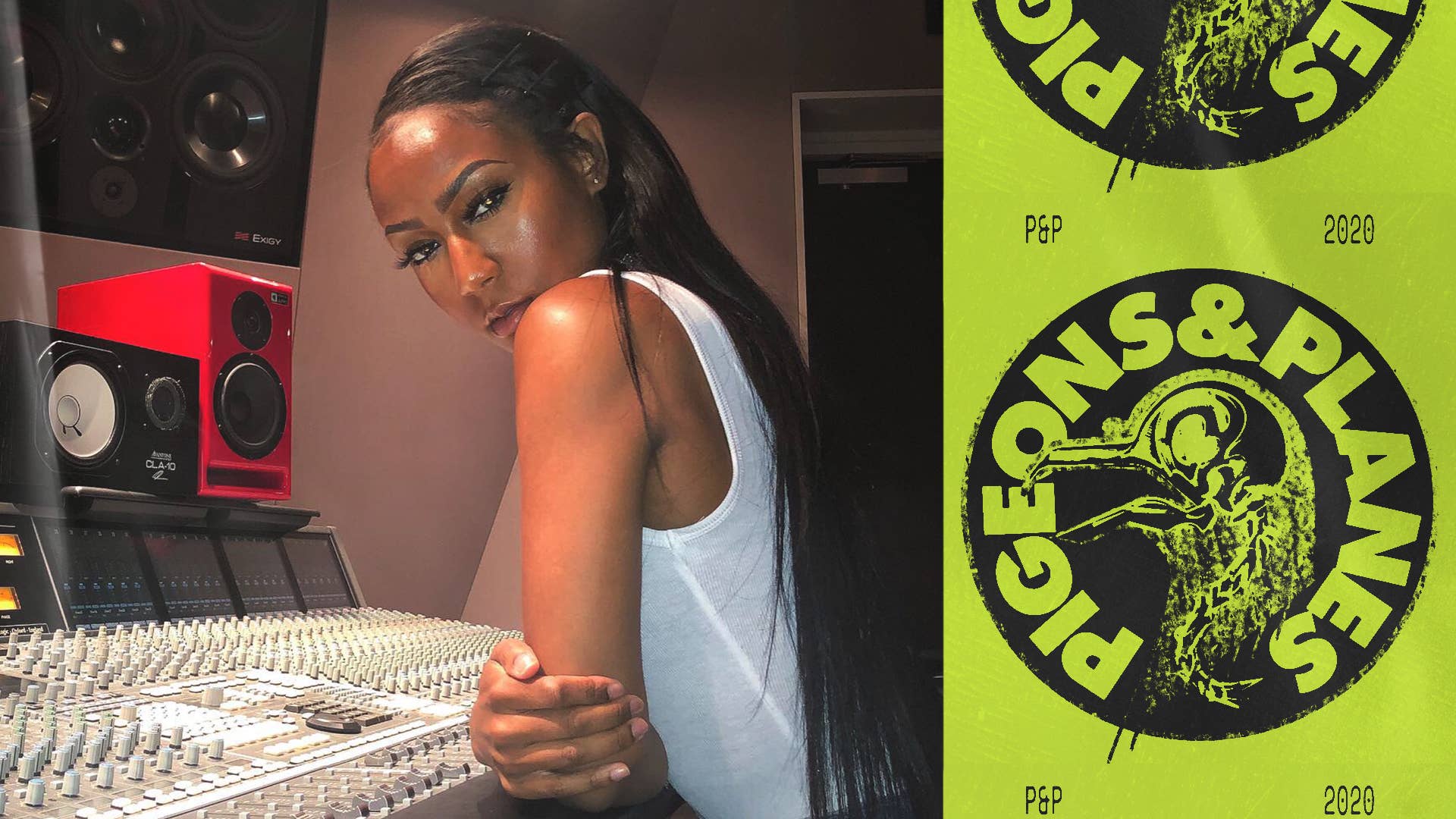

Over the last five years, Lil Uzi Vert has cycled through flows, hairstyles, and living locations. He’s delivered the most memorable verse on a No. 1 song, brought pop punk to the rap world, led SoundCloud’s upstart wave into the mainstream, and become a household name himself. Even though almost everything else has changed for the Philly rapper, one constant has been his go-to engineer, Kesha Lee.

Since she first began working with Uzi in 2015, Lee—who has also worked with Gucci Mane, Young Thug, Migos, Playboi Carti, Donald Glover, and more—has been behind the boards for every single one of his projects, bringing the most out of the rapper’s soaring vocals. But working on Uzi’s latest project, his long-awaited sophomore album Eternal Atake, was an entirely different undertaking. Recorded over a two and a half year period, the road to the album’s completion was a difficult journey that involved Uzi saying the album was finished multiple times, very publicly expressing his displeasure with his labels, and recording a lot of incredible music.

Along the way, Lee was interactive with Uzi’s fanbase on social media and they came to view her as a reliable narrator in what was otherwise, from the outside looking in, a constantly confusing process. But, following her on Twitter over these past few years, what stands out most is seeing the hard work behind the glamour of recording one of rap’s most eccentric stars—from sleeping on studio floors to lugging tons of equipment around the country. Over time, Lee has come to fill a unique role for Uzi that she’s referred to as “creative production engineering,” handling everything from sourcing beats, recording, adding additional production, sequencing songs, mixing, and more.

Over the phone during her quarantine in Atlanta, the Grammy-winning engineer opened up about the long road to Eternal Atake and what it took to get the album to our ears.

Tell me about how you first started working with Uzi.

I was a freelance engineer working at different studios and one of those studios was Means Street [the Atlanta studio owned by DJ Drama]. I was doing a songwriting session there, and Don Cannon came in and saw me working. He was like, “I got this artist I want you to work with.” I had a session with Uzi and it went really well. We both liked working with each other, and I loved his music. I told [Cannon] that him and Gucci were my favorite artists. From there, we locked in and started working all the time.

How do you think working with artists like Gucci and Young Thug prepared you for working with Uzi?

Learning how to work fast and adapt to different artists’ way of recording, going through a bunch of songs within a day. I remember recording Thug one time, and we recorded seven songs in one night—then after he was done, I had to record other artists that were in the studio. That helped me prepare for working with a large number of songs in one session.

At what point did you go from working with him to being his in-house engineer?

While we were at Means Street, whenever he had a session, I would be on that session. But then when he went to Philly [in 2017], that kind of pulled me out of Atlanta, and then I was solely working with him.

So you really had to uproot your life in Atlanta. What was that like and what went into that decision?

My life changed drastically. At first, I was really sad and depressed because I had never been to Philly. In Atlanta, I got to move around and work with a lot of different artists, and I was in the comfort of my own home. Some nights, I would sleep at the studio, but I could still come home and shower.

Leaving Atlanta and going to Philly, it took me out of all of that. I’m living out of a hotel, learning how to live on the road, trying to figure out how to pack what I need without carrying too much. The whole balance of my life got thrown off. At first, I was able to go home every now and then, like I would fly out on the first flight in the morning and then take one of the last flights back to Philly to work with Uzi that night. But then it got to where I wasn’t going home at all and it was like, “How do I create a balance?”

What were those early sessions like for Eternal Atake and how did you start to find that balance?

The first couple months, I would record Uzi and then go back to the hotel. Then, we started just staying at the studio. I started sleeping in the storage closet [laughs]—that way, I could still be close by if anybody needed me, they could call on me and we could go work. But the employees at the studio would try to get in the storage closet in the morning and the door wouldn’t open because it was so small. They would feel so bad trying to get past me to get something, but I also felt bad because I knew it wasn’t a place to sleep.

Once we started to get a little bit of a tracklist for the album, I couldn’t work in the main room because the producers were still making beats for him on the speakers. So I moved into the live room, where they had little booths, and my set-up got way better. I set up my air mattress in there, I had a laptop with some speakers, my Apollo, I started buying more gear so my workstation got cooler, I had a little tea kettle, an air diffuser. I started drawing when there was down time. I used to do ballet, and I started to pick it back up. I’d go off to the side and stretch or dance. I tried to find ways to balance everything out.

At the beginning of 2019, Uzi posted a story on Instagram that made it seem like he was quitting music. What was going on around that time and how did that affect your work?

I learned about that from Instagram how everybody else did. It didn’t really affect anything too much. I feel like maybe he was just frustrated. I’m not too sure what goes on. I just stayed there and was on-call until he was ready to get back in and record.

We talked about the struggles involved with moving to Philly and creating a new balance between work and life there. Were there any points where you felt like quitting?

Honestly, yeah. I love working with Uzi but there were so many other things going on that made my job not fun like it used to be. I was hanging in there so I could keep working with him because I enjoy working with him and there was something that we started that we needed to finish.

What were those outside things that contributed to making it not fun?

The music industry is a tough place to navigate and when you don’t know certain things, or have people that will look out for you, it makes it even harder. I think that’s what I wanna say without really getting into it.

Besides the location and the studio, what was different about working on Eternal Atake and recording Uzi’s early mixtapes?

There’s things that you don’t realize that play a big part in a project. Stuff like Luv Is Rage—I don’t even remember feeling like we working on a project. We were just recording, he would pick the songs, Cannon would give me a week or two to add whatever I wanna add, and then it would be out.

Over the past few years, you’ve been really interactive with Uzi fans on social media. What’s that experience been like?

At first, it was fun. Music was coming out and his fans were happy. Then they got impatient and they didn’t know who to be mad at so they just got mad at anybody associated with the situation. I kind of fell back on interacting. It doesn’t bother me though—I actually read a lot of what they say. It helps me with my job to understand what they like and don’t like. I have an understanding of his fanbase so when certain things happen and they come at me, or come at other people, I sort of understand. I think they just want to know certain things and, if you’re up front with them, then they’re pretty understanding.

Were there any points where you found yourself getting frustrated with the fact that music wasn’t coming out?

In the very beginning, I think I didn’t understand why it wasn’t dropping because I was just one part of it. But I started to realize that if I worked on something and it didn’t come out for years, I think the most important thing is that you enjoy the process and the people you’re around are enjoying the process and they’re happy with the finished product. It could’ve not come out for another year. I just wanted everything to be the way [Uzi] wanted it.

Some fans seem to believe that there were a bunch of different versions of Eternal Atake. Is there any truth to that?

No, some songs just got changed out. There was a tracklist pretty much the whole time we were recording, so if he recorded a song he liked better than another one, it would get replaced. There were songs that were still on that first tracklist that were still on the album. For the most part, we were still working and you fall in love with a new song and replace another. It’s not like it was a whole new version.

The skits in between songs of Uzi getting abducted tie the album together. How did those start to become part of the process?

I was trying to think of another way to add in a creative element. The older versions were way longer. I had started on the idea but, at one point, Uzi went in and improvised a whole scenario that was like 20 minutes long. I thought it was so cool. It was more dialogue and more of a storyline. I knew the skits couldn’t be too long so I chopped it down but, even then, they were still around a minute and a half. They took like a year for me to do but then, a week before the album was due, I had to change the whole thing and cut them down to around ten seconds.

At what point did you start to feel like you all were getting close to the finish line?

I felt like that when we were still recording and there were songs getting replaced. For the most part, he’s always gonna be recording but, once he had the tracklist where he wanted it, I had 14 days to finish the mixing and put everything together.

I’ve finished out albums before but there’s usually a lot of people involved—the A&R and the executive producer. This is the first time that it was really just me and the artist putting the whole album together. I logged what studio we were working out of, I was hitting up producers; if the gear that we used was different than what we usually used, I would log that. He would do the sequence, and then I would go back and adjust it so it would fit with the skits.

Looking back over the past few years, are there any sessions or moments from recording that really stand out to you now?

I think the session where he made “Homecoming” stood out the most to me because he pretty much had the tracklist, but he wanted one more song. Bugz [Ronin] was in the studio, Uzi really had an idea what kind of beat he wanted, and it came out so fire. That’s one of my favorite songs on the album.

The session with Syd was pretty memorable. Syd is the reason I got to go out of the country [to Berlin for Red Bull Music Academy in 2018] for the first time. Just to see her in Uzi’s session was so cool, and the fact that he wanted her to be the only feature on the album. It felt like a real full circle moment.

You tweeted out an email for beats a while back and then recently wrote that one of the producers who sent beats to the email actually ended up producing “Prices.”

Uzi made an email for beats first [in 2017], but then it got so crazy full that I ended up making another one. I tweeted it but then my account was getting locked because there was so much traffic. He would have his day where he would want me to go through and play the beats in the email and, whenever he liked one of the beats, I made sure to keep playing that producer's stuff. It got to the point where he got familiar with this producer [Harold Harper], and he was like, “Why don’t he ever come out here?” So I got him a ticket, and he came. That was the best feeling.

What did it feel like to wake up to the album being out on the day it was released?

I definitely didn’t wake up to it because we were working on it until the last minute. I think I took a nap and then woke up a few hours after it was already out and was reading through all the comments and tweets. It was a weird moment. I was working on something for two and a half years and then it was just over.

Then, almost as soon as the album came out, the deluxe version became a thing.

I found that out from Twitter. Deluxe’s are usually a couple songs so it was something to give his fans that they’ve been wanting. They call them “holy grails” — these snippets they’ve been wanting. It turned from a few songs into a 14-song tracklist.

Some fans seemed pretty upset about the mixes of those really sought-after songs.

I thought some of their notes were kind of legit. With the album, I had more input and involvement. The deluxe—I think they were wanting to give me a break because we had just finished the album. So someone else did the mixing for that, and I guess it wasn’t what the fans were used to hearing. They assumed that I had done it, and they were coming at me crazy.

Did you end up redoing any of the mixes?

I did but then this whole virus stuff happened. I don’t know if they’re going to be added.

After dedicating two and a half years of your life to this album, do you feel like you’ve had a chance to decompress?

My life is already crazy so, with the virus, it’s been like leaving from craziness into more craziness. When I came back [to Atlanta], my focus wasn’t trying to work. I’ve been working for two and a half years straight. I missed my first Grammys ceremony—the first time I get invited and I win— to work on this album. I have nieces and nephews I haven’t even met yet. I enjoy what I do but it’s like, one thing shouldn’t get that much of your life. I’ve just been trying to get my personal life together, relax, and find that balance again because that was crazy. [Laughs]